A short history of interurbans in the Lower Mainland

A short history of interurbans in the Lower Mainland

Today, I’m pleased to present a look at the history of interurbans in the Lower Mainland.

Lisa Codd, the fantastic curator at the Burnaby Village Museum, helped me put this article together. She first shared a luncheon menu and programme from the 1937 Pattullo Bridge opening in January – and this is a continuation of that collaboration, to explore transit history and Burnaby’s archival holdings!

What’s an interurban?

An interurban is another name for an intercity electric railway that runs at street level.

Interurban trams were like streetcars, except larger and more powerful. They also hauled freight between cities, although passengers were always the priority.

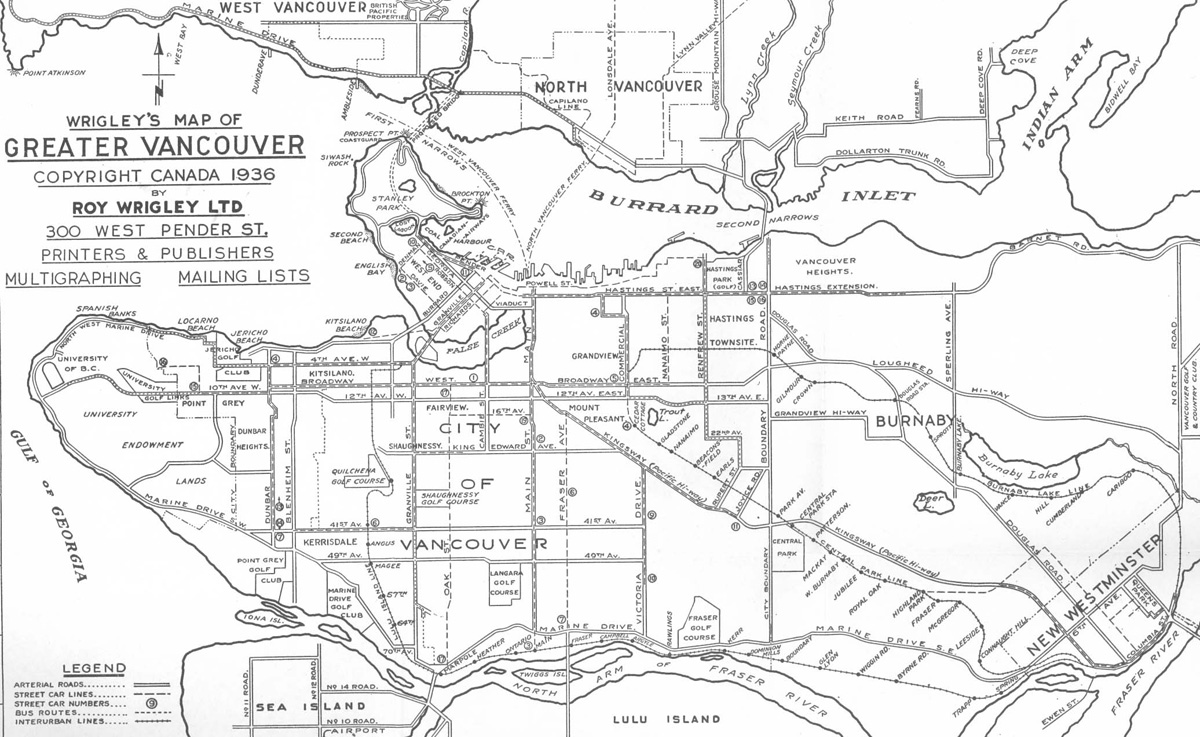

An interurban system ran in Greater Vancouver from about 1891 to 1958, with five major lines:

- the Central Park Line (similar to today’s Expo Line),

- the Burnaby Lake Line (similar to today’s Millennium Line),

- the Lulu Island Line (similar to today’s Canada Line)

- the Westminster-Eburne Line (connecting Marpole to New Westminster)

- and the Chilliwack Line (connecting New Westminster to Chilliwack)

In the United States and Canada, interurbans were immensely popular, as they were a vast improvement on horse-drawn transport, and offered a clean, cheap alternative to steam railways.

They also stopped almost anywhere (check out the number of stations on the Central Park Line on the map), and ran far more frequently than steam trains (half hourly and hourly service was the norm.)

As well, development patterns followed the railways. The street railway network permitted families of modest means to settle in outlying areas, where land was cheap enough to enable them to acquire their own property, and established new communities around the stations in the process.

The interurban network was a boon for farmers and local manufacturers alike and opened up a whole new world of possibilities to many rural families.

How interurbans started up in Greater Vancouver

|

TIMELINE

April 26, 1890 August 1, 1890 April 20, 1891 June 3, 1891 |

In the 1890s, local entrepreneurs launched electric railways in Vancouver, New Westminster, and Victoria, eager to cash in on the promise of future growth in the major cities of the time.

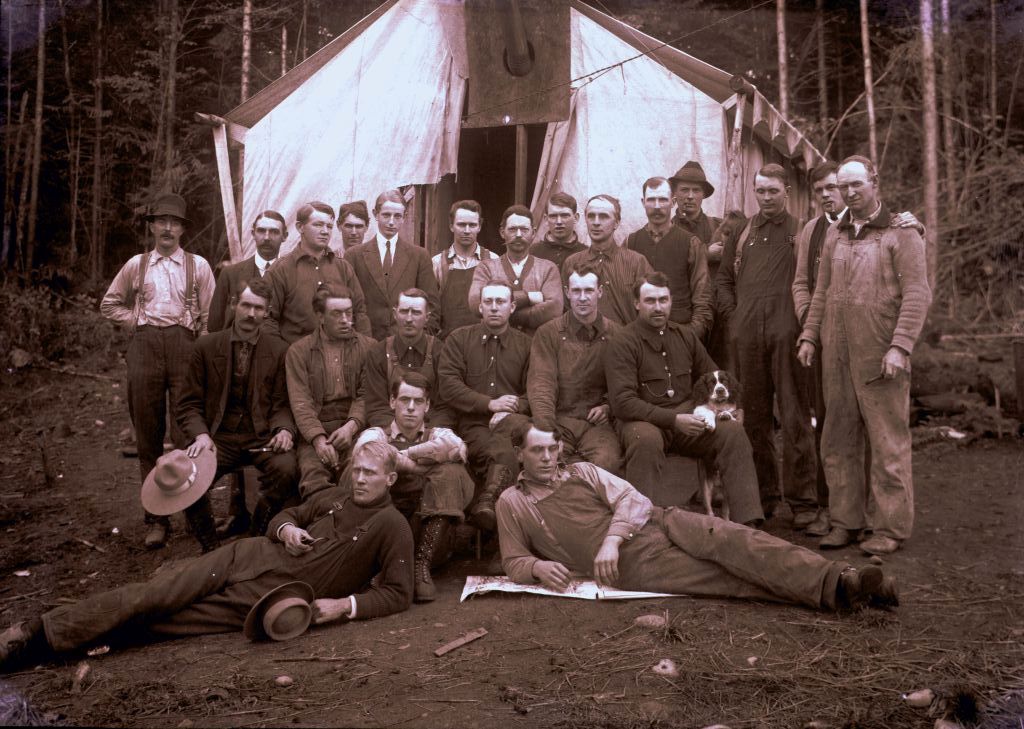

In the Burnaby area, two companies started building electric rail in 1890: the Westminster and Vancouver Tramway Co., which undertook the ambitious project of building the first real interurban line from New Westminster to Vancouver, and the Westminster Street Railway, who eventually built streetcar service and installed electric lighting in New Westminster.

By April 20, 1891, both companies merged to form the Westminster and Vancouver Tramway Company. Local entrepreneurs Henry V Edmonds (yes, of street and station fame), David Oppenheimer, Benjamin Douglas, and Samuel McIntosh, were the directors, all of whom had extensive real estate holdings in the area.

Interurban service launched on June 3, 1891, travelling the Central Park Line from New Westminster to eastern Vancouver. It wasn’t accidental that the new line travelled through the property of many of the directors and more — there are numerous examples of the close relationship between real estate promoters and the street railway!

Recession throws a spanner in the works

However, early rail companies in B.C. got a bit too caught up in the booster mentality.

To them, the future had boundless possibilities and nothing could go wrong. The snag was that a street railway and interurbans required a significant amount of infrastructure: rails, powerhouses, as well as the cars.

The economy was much more cyclical then, and when it plunged into a recession in 1894, these companies did not have the resources to handle it.

Profits disappeared and local capital dried up. They all had insufficient funds to make costly repairs—and the Westminster and Vancouver Tramway Company was no exception.

When lightning struck the Company’s dynamo, which generated electricity to power the interurbans and streetcars, the repair costs bankrupted the Westminster and Vancouver Tramway Company. On top of that, reducing service was not an option or their service agreement with the municipality would be null and void.

The company went into receivership in August of 1894. Revenue from the sale of electricity offset some of the losses, but the companies could not survive the recession.

Eventually, all of the B.C. electric rail companies were taken over by the Consolidated Railway Co., which incorporated on April 17, 1896.

But just after it launched, the Point Ellice Bridge in Victoria collapsed under the weight of a fully-loaded streetcar, killing fifty-five people. With heavy damage claims pending, the company foreclosed on October 13, 1896.

The rise of the B.C. Electric Railway Company

|

TIMELINE

April 15, 1897 September 2, 1898 |

However, Robert Horne-Payne, vice-president of the Consolidated Railway Company, wouldn’t give up on rail in B.C. that easily.

He acquired new investors, and in April 1897 he launched a new company to run electric utilities, lighting, and streetcar services in B.C.: the British Columbia Electric Railway Company (BCER).

Horne-Payne controlled the Company from London, England, while Frank S. Barnard, the managing director, was based in Victoria.

From the beginning, the BCER was on sound financial footing. The directors were very cautious; any service expansion would have to be profitable.

Between 1897 and 1913, over a million pounds was invested in the BCER, for the most part by British citizens. This pattern was repeated throughout the country—Canadian, provincial and municipal government guaranteed bonds were extremely popular with British investors during the period 1890 to 1914.

Throughout the 1920s the BCER continued to invest in new Hydro Electric projects such as the Bridge River Project near Lillooet, and new transit companies such as the BC Motor Transportation Company.

Key dates from BCER system growth in the 1900s-1930s

April 2, 1903

As the system grows, the BCER can’t get enough new cars to meet its needs. The company decides to build its own cars, building a new car barn and large factory at the foot of the 12th Street hill in New Westminster. (The Petro Canada gas station is located on the site today.) The first streetcars built here go into service on August 2.

June 4, 1904

Vancouver streetcars begin operating on hydro-electric power, generated by the BCER subsidiary Vancouver Power Company at Lake Buntzen.

January 20, 1905

The BCER announces it will lease the Vancouver and Lulu Island Railway from CP Rail, and begin service from Vancouver to Richmond. First, they need to electrify the line and install trolley wire, as well as build a substation at Eburne.

September 3, 1906

The fourth (and smallest) streetcar system in the BCER network begins operations in North Vancouver, after residents petition the company to start a service. Power lines are strung across the Second Narrows.

September 24, 1906

B.C. Electric general manager R. H. Sperling announces that the Chilliwack interurban line will be built.

October 1909

Construction technically begins on the Burnaby Lake interurban line.

November 6, 1909

The streetcar line on Hastings Street is extended to Boundary Road.

November 15, 1909

The Eburne-New Westminster line opens for regular service; passenger interurbans meet the Central Park line at 12th Street Junction.

October 3, 1910

The interurban line to Chilliwack is officially opened.

|

|

|

|

|

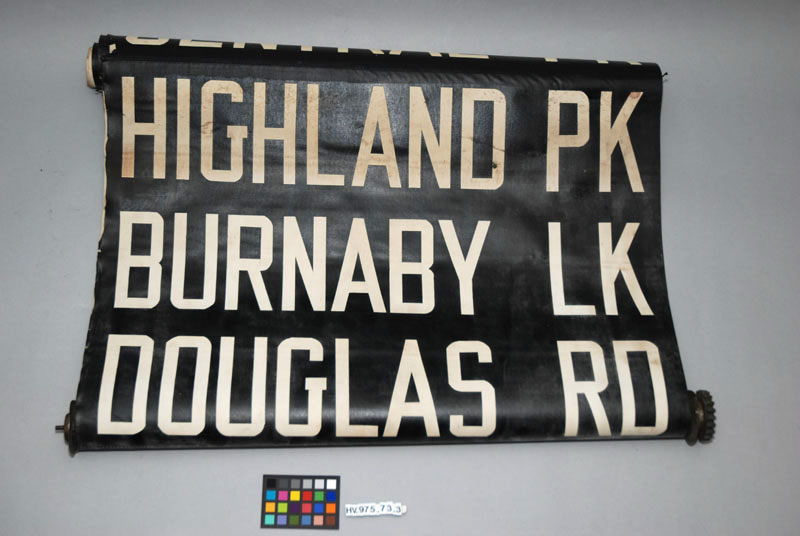

Destination rollers from an interurban tram. These are part of the Burnaby Village Museum’s collection. |

February 27, 1911

The last spike of the Burnaby Lake line is driven at Hastings Townsite. A car of officials and guests make the first trip from Vancouver to New Westminster on March 1.

December 22, 1913

The Hastings Extension line opens in Burnaby, running along Hastings Street, from Boundary Road to Ellesmere Avenue.

February 12, 1924

The BCER forms the British Columbia Rapid Transit Co. Its mandate is to purchase motorised passenger and freight lines that are operating in competition with the interurbans between Vancouver, New Westminster, and Chilliwack.

October 1, 1924

Last run of the Saanich line over in Victoria. Much of the rolling stock is transferred to the Lower Mainland where it is modified for use on the local system.

1925

The BCER incorporates a new enterprise called the B.C. Motor Transportation Company which brings under one banner all the independent companies: Pacific Stage Lines, Yellow Cabs, Triangle and Circle Sightseeing Tours.

November 15, 1937

The Pattullo Bridge officially opens.

December 4, 1938

Last day of service for New Westminster streetcars. Faced with a growing population living in areas not serviced by the streetcar, New Westminster converts completely to motorbuses; the trolley poles, tracks and wires are all removed from Columbia St. The interurban lines are now the only rail transit still entering the Royal City.

The end of the interurban service

While it continued to maintain interurban and streetcar operations, it is clear the Company realized that with no expensive permanent tracks to install and maintain, motorized transport was the way of the future.

At the end of the 1930s, the popularity of streetcars with the public was also starting to decline. As the Depression drew to a close, the BCER had a system that was over 40 years old, matched in age by many of the streetcars. Commuters began to appreciate the comfort and convenience of their own cars.

By the end of the Second World War, the BCER faced the need for a thorough modernization of its fleet of transit vehicles. A decision had to be made about renewing the ageing streetcar fleet, along with all track and electrical equipment—but this was a dubious investment for a population that was returning to automobile travel.

Instead, the company decided to launch a 10-year program to convert the entire transit system “from rails to rubber,” from streetcars to rubber-tired buses.

On August 16, 1948, conversion to trolleybuses began. The first trolley route, Fraser-Cambie, operated from Fraser Street and Marine Drive via Fraser, Kingsway, Main, Pender, Seymour, Robson and Cambie Street to 29th Avenue.

In 1955, Vancouver’s last streetcar made its final run. And in 1958, the last of the interurbans finished up service in Steveston.

And on August 1, 1961, the Province of British Columbia took over the B.C. Electric Railway, creating a new Crown corporation called the BC Hydro and Power Authority.

Want more history?

Thank you again to curator Lisa Codd for all her help with this article!

She’s pointed out that you can find all of the historic images in this article and more at the Heritage Burnaby website. This comprehensive resource brings the City of Burnaby’s archival documents, photographs, museum artifacts, and heritage landmarks under one virtual roof for easy public access.

And of course, visit the Burnaby Village Museum for more history treats! Again, it’s is an open-air museum that recreates life in 1920s Burnaby. It’s currently closed, but will be open for spring break on March 16-22, and for the summer season on May 2. (Check the museum’s website for admission costs and more!)

For more on local transit history, take a look at the books of Henry Ewert – he’s a local historian who has written books such as The Story of the B.C. Electric Railway, Vancouver’s Glory Years: Public Transit, 1890-1915, Victoria’s Streetcar Era, and The Perfect Little Street Car System: From Ferry to Mountain in North Vancouver, 1906-1947.

You can also try TRAMS, the Transit Museum Society, who run a real-life restored streetcar on the Downtown Historic Railway. And B.C. Hydro’s Power Pioneers association runs a great history website that includes info on streetcars.

And you can’t beat Chuck Davis for more regional history – check out his website, and his terrific series in Regarding Place magazine called A Year in Five Minutes, which showcases stories from each year in Lower Mainland history.

Hope you enjoyed this look back at the interurbans!

Thanks for the great article.

My father, who grew up in Burnaby in the 1920s and 30s, used to tell a story about a friend of his, by the name of Jack Guppy, who stole an Interurban car one night. It went something this … he was trying to get to Vancouver from Burnaby late one night to check out a jazz club (Jack Teagarden???). He climbed on board an empty car and waited for the driver. Nothing happened for some time, so he decided to drive the car himself into Vancouver. He drove it all the way along Hastings into town! Apparently, he just left the car where he stopped and went to his show. I don’t know if he used it for a return trip or not!

Could be a bit of a tall tale, I suppose, but I’ve often thought what a great story it is! Wish I had more details. Neither my father nor JG are around anymore to verify the details.

Cheers!

I have keys to the tram on Kingsway and Edmonds my grandfather was the conductor Alvin Burtch

Thanks David — that is a fantastic story! Perhaps I’ll ask a few old-timers about it next time I have a chance :)

[…] if you are interested in the system that we tore up here at about the same time take a look at the Buzzer blog Possibly related posts: (automatically generated)Threats to Transit in a Warming World: Heat, […]

Hi Jhenifer!

Great article…and thanks for mentioning TraMS.

On a note re: David Morton’s comments.

I sincerely have my doubts on Jack Guppy’s story of “stealing an Interurban one night to get to a show.”

To begin with, every motorman carried what was simply referred to as a brass key. It looks similar to an open end wrench.

It would have been a violation for the motorman to have simply left in the car while he stepped away.

Secondly, traversing the line to downtown would have involved passing through switch points and trolley frogs…something that entails skill which is accomplished through training.

Lastly, as the Interurban came closer to downtown, the interurban “shared” track line with Vancouver’s streetcars in operation and would have required knowledge of the rules operating on the same line without causing an accident to occur.

As Mr Morton kindly points out, it was in all likelihood, simply a tall tale… Yet a fantastic story one made to impress the youngsters back then no doubt! =)

Jerry Plante

Downtown Historic Railway Inspector

it is very interesting. I wonder if the old terminal pub at the bottom of 12th st. is due to the station that used to be there.

I would say it exists because of the busy waterfront at that time. All the longshoreman, the crews from aboard ships and related workers needed a place close by to have a beer and unwind. Also just around the corner from the terminal pub was/is the Garfield hotel. Unknown if they had a beer parlour or the patrons went to the terminal.

[…] Want One Port Mann Bridge, or a Light Rail Metropolis? [The Tyee] A short history of interurbans in the Lower Mainland [Buzzer Blog] Council peddles public bike sharing concept [The Vancouver Courier] Integrity […]

Thanks for the clarification on the story, Jerry :)

This was a total treat to read – so glad folks took snapshots back then to tell us about their daily experiences. So … how do we get the InterUrbans rolling again? … Or i am just a dreamer ;-)?

That’s pretty cool… but its kinda funny how even 100 some years ago i would of had 3 or 4 ways to get home from downtown… but i guess the old saying is true: “history repeats itself”… quick little point the the old central park line tracks are still there… at least from metrotown to 22nd street… but there are some places where the tracks been removed… mainly parts where the tracks cross streets… but other than that its still there…

This is a really awesome article…. the location selection about transit lines haven’t changed all that much in the last 100+ yrs. that’s just amazing….

my grandfather pete tumac worked on the railline and in the early fifties i used to go to work with him and take the train from newwest to chilliwac, i ended up working there as a brakeman and conductor in the 70’s and 80’s

[…] throughout the region and served it as one unified transit system for about 60 years. (Here’s a past post about B.C. Electric and its […]

[…] The women hired during this time were called “conductorettes.” They worked on the streetcars, and only on the Vancouver routes—you wouldn’t find them on the interurbans. […]

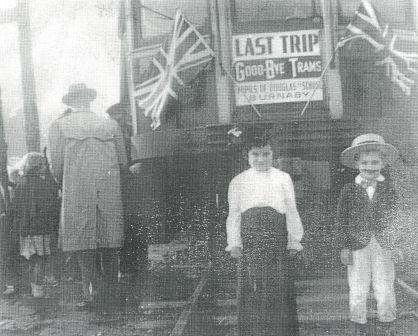

Having grown up in Burnaby I appreciated your references to the Burnaby Lake Interurban Line. At the age of 10, in October 1953 I, along with my Douglas Road School classmates took the last ride on that venerable tram. We went from Douglas Road out to Sapperton and back again. You brought back some memories and I still miss the old trams.

[…] this transit demonstration. Vancouver has a fine 60+ year history of streetcar systems (such as the Interurban) and I’m sure many would like to see this mode of light transit return to our […]

Our family lived off Hill street. We used to play along the tracks and put pennies on the track . We would walk along the track to Deer Lake.

This was in the early fifties. Nice place to grow up.

[…] bound to love it. Take pictures of the huge botanical animal sculptures, climb aboard a restored interurban tram, check out the miniature train set and grab a sweet treat at the old-fashioned ice cream parlour. […]

Nice site…

[…]here are some links to sites that we link to because we think they are worth visiting[…]…

Normally I do not read post on blogs, however I wish to say that this write-up very pressured me to check out and do it!

Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thanks, quite great article.

According to some old maps I found, when the Burnaby Lake Line was built, it did not go up Commercial Drive. It went towards False Creek.

A map showing the original route of the Burnaby Lake line can be seen here.

http://collectionscanada.gc.ca/pam_archives/index.php?fuseaction=genitem.displayEcopies&lang=eng&rec_nbr=3932441&title=Atlas%20of%20the%20city%20of%20Vancouver,%201912&ecopy=e010756495-v8

You have to download that map so that you can view it full size.

Don’t look at the Point Grey map.

View the one below it, in full size. Not screen size.

But I wonder where the Central Park Line originally terminated.

It did not connect with the Burnaby Lake Line on Commercial Drive.

Hello,

In the past number of years I have been looking for articles and also pictures and videos of the Interuban in Vancouver and area. I lived in Burnaby and took the Central Park Line starting at Royal Oak into Vancouver many, many times with my mom and dad. My dad was a veteran from WWII and was injured, he took me more that once on the line that went south on Oak Street Shaugnessy Hospital. Many times I pretented to operate the tram from the rear area as it rumbled along. Great memories. I am including the Central Park Line in my HO Scale Model Railroad. Can’t wait to see it operate. Thanks for these great memories.

thank you to Tom for the link to the original Map!

I have overlaid it on a current GoogleMap so we can see where the tram route was.

On letsgobiking.net

Does anyone know how late at night the streetcars and Interurban trains would have run in the early 1930s? In particular the lines along Hastings? I’ve been looking for schedules online, with no luck, and the Vancouver Public Library Special Collections are closed due to the pandemic.

Much thanks!