Fleet Overhaul Series, Part 4: High-mileage vehicle repairs

Fleet Overhaul Series, Part 4: High-mileage vehicle repairs

This is the fourth in a six-part series about Fleet Overhaul, the vehicle maintenance centre down at Burnaby Transit Centre. (Check out the first article on the body shop, the second about panel fabrication, and the third about the paint shop.)

Did you know we completely rebuild engines and transmissions for our conventional vehicles at Fleet Overhaul?

It’s true. Most engines are rebuilt for any conventional or articulated bus that has clocked 800,000 to 900,000 kilometres—it’s the central part of a high-mileage overhaul.

And transmissions are built and replaced in vehicles more frequently, usually when a vehicle hits 350,000 kilometres.

The high-mileage overhaul

In the two photos above, you can see the row of high-mileage buses being overhauled.

How do we fix them up? Well, first, mechanics at Fleet Overhaul completely rebuild the engine until they’re good as new.

While the engine is out, the back end of the bus gets a steam cleaning, reinforcement of its rails and structure, and a paint job. A licensed electrician also does rewiring and replacement of electrical parts.

After the engine is rebuilt and replaced into the vehicle, Fleet Overhaul staff then take the bus out for test drives to ensure everything’s in proper working order.

It takes about three weeks to overhaul a high-mileage vehicle. After this, Fleet Overhaul won’t usually see the vehicle again for engine work for another six or seven years.

Each year, Fleet Overhaul completes work on about 90 high-mileage vehicles. In 2008, the staff managed to overhaul 160 buses, as a small afternoon shift was added to help prepare for Olympic transportation demand.

Engine work

There are eight mechanics who build engines full time, and each engine is built by just one of these eight mechanics.

The mechanic’s name is then attached to each engine when entered into inventory, and there’s a definite pride in workmanship that comes with that. As overhaul manager Jeff Dow explains, each mechanic is very conscientious about the engine he or she produces, and feels quite personally responsible if an engine fails for any reason.

It takes about three and a half weeks to rebuild an engine, and Jeff says that 108 engines are built in an average year. In 2008, 120 engines were built, again in preparation for Olympic demand. (Due to cost savings, some engines are also bought new.)

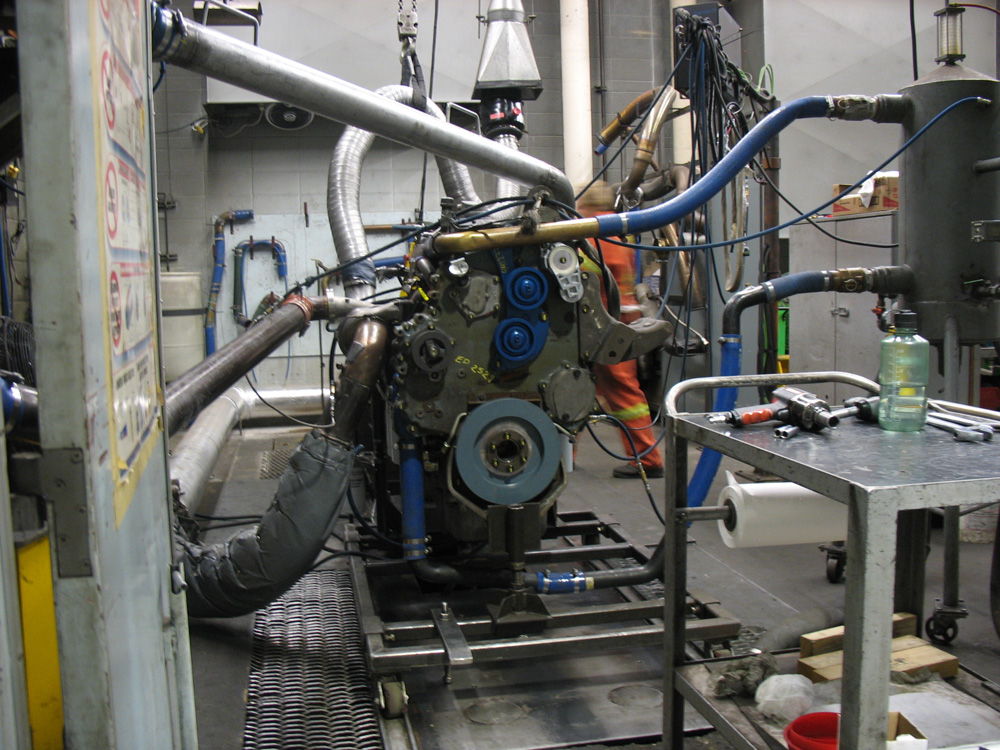

Once an engine is rebuilt, it is tested extensively in a Dyno, a testing facility that runs the engine through its paces and can reveal any possible issues. A computer simulates the terrain that the engine might face in the real world, such as a run down Hastings or up the hill to SFU, which is considered the most difficult terrain of all.

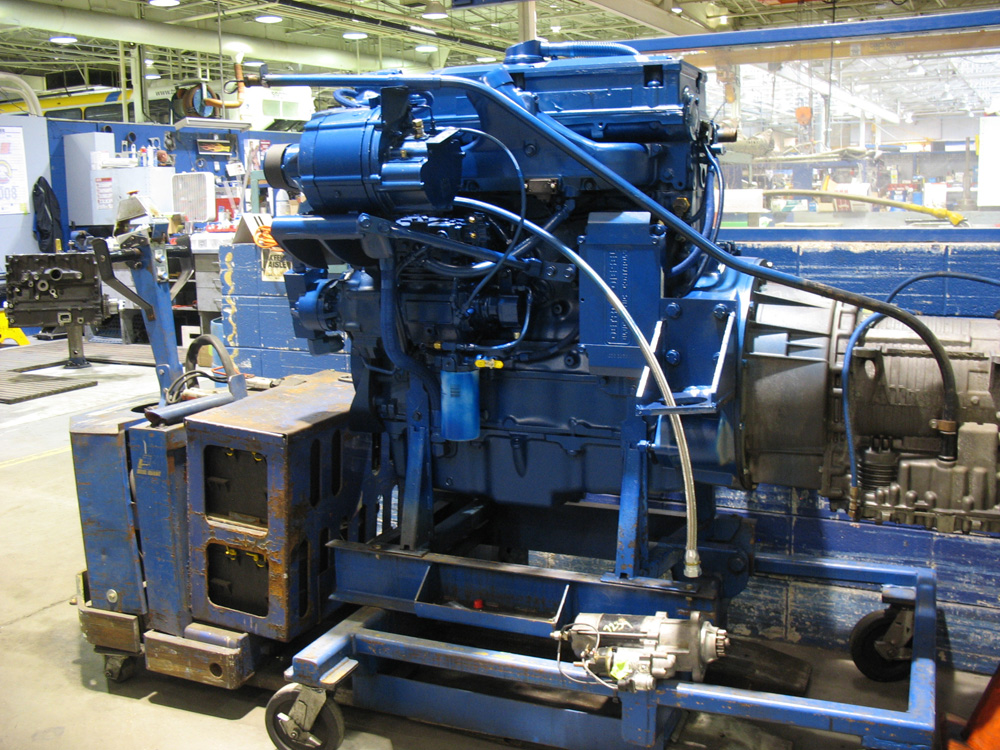

Once the engine has been fully tested, it is painted one of four colours – red, yellow, dark blue, and light blue. The colours help identify the type of bus it goes into, the parts needed for the engine, and the engine’s emission package. (An emission package dictates what internal components are used to build an engine. Regulations are always increasing so a different engine was built in 1996 versus 2000, as the regulations are more strict.)

Transmission work

Transmissions are also built by mechanics at Fleet Overhaul. (A transmission takes the power generated by the engine and uses it to drive the vehicle’s wheels.)

There are eight mechanics who build 220 transmissions every year. It takes less time to build a transmission, roughly 50 hours. But as I mentioned before, transmissions are replaced more often, usually around when vehicles have driven 350,000 km.

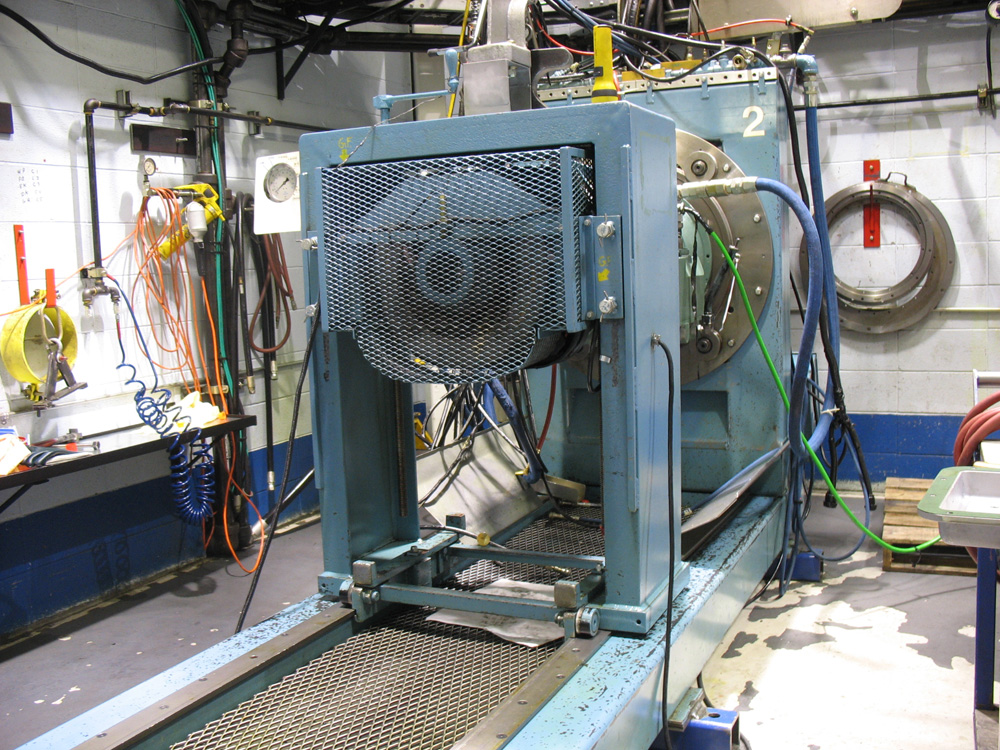

Transmissions are also sent through their own Dyno for testing, simulating the regional terrain including the hill up to SFU again. Jeff explained that coming down the hill with a full load of passengers can be very hard on a transmission!

All right, that’s it for the high-mileage vehicles! Watch for the next installment in this series, which will be about the warehouse and the vehicle parts that get created at Fleet Overhaul.

hey jen!

i lovethis article! though i have 2 questions:

1) whenever i get on those novabuses, i notice that the driver only opens the large door instead of also opening the skinny door. y doesnt he open both doors?

2)when are the new 2009 (hev) novabuses, the new de60lfr, and the new skytrains be in service?

Fascinating; as usual, great work with this series.

Speaking of test drives, this reminded me of something I’ve been wondering for quite some time: Once in awhile, I’ll see an out-of-service bus being driven around displaying “MW CHEC” on its rear route-number panel. What does that mean? Whom is it meant to inform?

My educated guess has been “maintenance worker check”, or something. But I’m sure the public at large is completely mystified.

Daniel: The front doors on the Novas are very large when split in half, this leaves a large gap which fare cheats can pass through. With the 80/20 door split, the driver can open a large enough gap for a single row of people to pass by. But when a stroller or wheelchair needs to be boarded, the driver can open the whole doorway for increased accessibility.

The new DE60LFR’s should be coming online in a couple of weeks, 4 of the buses have arrived and are being handed over to CMBC once they are tested. The Nova HEV’s aren’t coming until this Fall, although a demo one is running around right now.

Ben: “CHEC MW” simply means “CHECK MESSAGE WRITER” CMBC didn’t program the rear luminator signs properly so the error message shows up instead. West Vancouver programmed theirs to simply say “NIS”

Chris Cassidy

Following Daniel’s Novabus front-door split question: When the driver does not open the left skinny door, I cannot grab its handrail (on the reverse of the door) to help myself up the stairs (bad knees). I already have my pass in my right hand when it’s my turn to board, and I’m weaker on that side, so it’s counter-intuitive to grab the railing on the right-side door. Otherwise I hold up the line when I have to get my pass out at the top of the stairs. I’ve noticed a few elderly passengers struggling with this as well, having to grab the left rubber door-gasket when it stays closed.

With Translink patting itself on the back about making the system so accessible to the disabled, I would like to think that a basic thing like handrails for passenger safety would be a little more important to them than keeping that door closed to avoid fare cheats squeezing in, which in 20+ years of boarding buses nearly every day, I have only ever witnessed 2 or 3 times! The drivers seem to automatically open only the one door, and they act like it’s a pain in the butt when I ask them to open the left one too (I don’t look particularly disabled). Just something I would like Translink to consider (opening both doors on the Novas for boarding every time, like every other type of bus in the fleet can do). Thanks. :)

Thanks Reva. I’ll forward this on to the appropriate dept!

Kinda curious on the policy with drivers overriding the rear door interlock (aka the doors are still closing as the bus is taking off) It seems more drivers are doing this and is becoming a safety issue. This morning on the 701 (14/701 P8088) The driver did that and someone about got caught in the door as the passenger was exiting. As far to my knowledge. The “override” switch is not to be used. Maybe some clarification would be great. Thank You

Thanks Jhenifer. :)

Also, I forgot to add that if the driver kneels the bus, that doesn’t always help, because I need the handrail to steady myself as I step up, especially if the driver parks too far away from the curb.

Thank you, I’ll stop ranting now. :)

wow thanks guys! now i know why the driver doesnt open bth doors! =D but one more question though: why is it that i rarely see trolleybuses at joyce station? i mean i notice that the trolley wires are never used! it would be nice if there were some trolleys there to cover up the smell of diesl!

Daniel:

The reason that you seldom see trollies at Joyce is that the 41st Line no longer has any runs that go only to Crown. All of the runs now go to UBC at least once during their work day. The only use for the wire at Joyce now is for a short turn of the 19 Line

On weekends, only one out of three 41 buses goes to UBC. Many of the runs could easily be trolley buses, but who knows why CMBC doesn’t want to save money?

Sungsu:

I believe it cost more to run a trolley per km then it is to run a diesel.

It was suggested in the Vancouver/UBC Area Transit Plan that when the 43 is replaced with a B-Line that runs 7 days a week, they have my the 41 terminate at Crown on the weekends, and would restore trolley buses on the 41 at those times. Whether that actually happens is anybody’s guess, but that’s what the consultants recommended in the report.

Corey