A field guide to transit debates: notes from Jarrett Walker’s talk, Wed Aug 4

A field guide to transit debates: notes from Jarrett Walker’s talk, Wed Aug 4

Jarrett Walker week continues with my summary from last night’s talk! And what a talk it was: if you only ever read one post on the Buzzer blog, make it this one, as it provides an unbelievably clear practical foundation for thinking about transit and many other debates.

Again, for the uninitiated, Jarrett is a public transit planning consultant in Australia who writes the fantastic transportation blog Human Transit. Last night, he gave a talk called “A Field Guide to Transit Debates” presented by the SFU City program, outlining some basic strategies and concepts to help clarify debates about transit.

Some key overview items for the tl;dr crowd:

- This talk was very much intended as a field guide — no recommendations one way or another, just ways to identify and talk about transit debates in a useful manner.

- Jarrett provided a “spectrum of authority” with you can use to judge statements made about transit. On what basis, or authority, is each statement being made? The spectrum spanned generally from feelings to facts—ie. “I feel strongly about this” vs “This is a fact of geometry.” The caveat is that facts of geometry/physics will always be true, while feelings and perceptions may change as time goes on.

- There are some immutable laws of transit geometry that we could use in transit debates so that we all start from the same framework, as well as some basic concepts like “Density, not total population, drives transit demand.”

- The concepts of vision and practicality drive many transit plans — a good balance between the two is needed to create workable transit plans for the future. (Too much of one or the other can leave us stuck.)

- Also: Jarrett’s apparently writing a book on this subject this fall!

Again, Jarrett was a fantastic speaker and was amazingly ready with an intelligent response to any transit question asked! Questions ran the gamut from road pricing to faregates to how transit agencies should be structured too. I thought it was a bit like seeing an oracle of transit speak: bring him your transit questions and concerns, and he will immediately have an insightful, helpful thing to say.

Read on for my full notes!

A Field Guide to Transit Debates

Jarrett started by explaining that the field guide was a useful metaphor for the substance of his talk — a field guide presents categories for organizing the apparent chaos in nature, offers tips for identifying these categories, and helps make connections between them. As well, the field guide only describes: it doesn’t judge or make recommendations one way or the other.

The chaos of transit claims can be very intimidating, so with Human Transit and the book he’s writing this fall, he’s hoping to help provide a way to organize these claims and help us have more useful debates.

The spectrum of authority

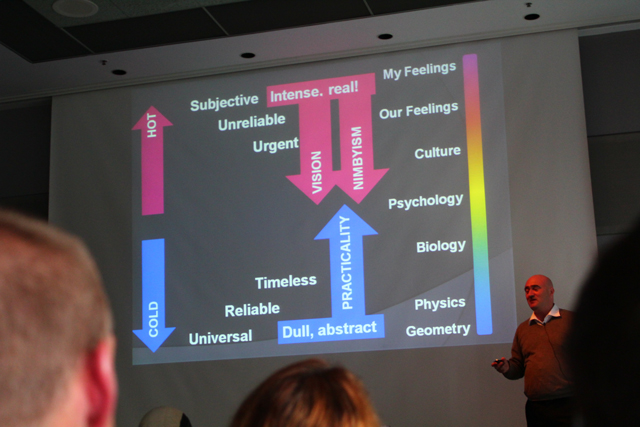

A spectrum can help us show how things related to each other. This spectrum was one Jarrett called “the spectrum of authority,” and helps you understand where different statements about transit are coming from—ie, “what is the authority behind this statement?” This can help us orient ourselves better around transit debates.

Here’s a written description of the spectrum, which you can see in the top picture. From top to bottom, the spectrum categories are: My Feelings, Our Feelings, Culture, Psychology, Biology, Physics, and Geometry. The spectrum was described as “Hot” at the top and “Cold” at the bottom — Jarrett said that as you went from cold to hot, relevance decreased but intensity of authority increased.

Jarrett explained that the items in the Cold section are timeless, reliable, universal statements of fact. Statements based on geometry and physics will just always be true. But as you go up the spectrum, however, the types of category get a bit more subjective, running all the way from biology to psychology, to culture, our feelings, and my feelings — the most subjective and intense. That end of the spectrum, the “Hot” side, provides a basis for statements that is more subjective, unreliable, and urgent. (A bit more description: Jarrett described “culture” as an idea made up of generalizations that we hold about the society that we live in. For “Our feelings” he described this as our personal echo chamber — the people we know and talk to.)

The thing to remember though, is that the “colder,” scientific facts will always overrule “hotter,” more subjective authorities. So even if our feelings or our perceptions of our culture change over time, those basic “cold” facts about the transit choices we’ve made will still be true.

To illustrate the spectrum, Jarrett gave the example of statements made around urban streetcars, identifying the authority behind the statements (apologies if I got the statements wrong, I was scribbling furiously):

| Authority behind the statement | Statement |

My feelings: I love how streetcars look

Psychology: Streetcars are a more permanent type of transit

Biology: Rail is a more comfortable ride

Physics: Replacing buses with streetcars is not a mobility improvement

Geometry: In mixed traffic, many situations will trap a streetcar that don’t trap a bus.

Jarrett said he wasn’t trying to condemn streetcars—if you want outcomes other than speed, they are a fine choice. But you can only go so far with marketing to hide the basic “cold” facts about their service.

As an aside, he expanded a bit on the Geometry statement (“In mixed traffic, many situations will trap a streetcar that don’t trap a bus”), and said that diehard streetcar fans will respond to that with “Drivers will give way to streetcars.” But Jarrett said that response takes its authority from “Culture” — it’s a cultural response to a geometry problem, but geometry will always outlast the perceptions of culture that we may have today. Culture may change: the geometry around streetcars won’t.

Practicality and vision

Zooming out a bit, Jarrett talked about the entire spectrum and said arguments coming from the “hot” side of the spectrum are generally characterized as having an emotionally gripping “vision,” while the “cold” side is focused more on cool practicality.

(Side note: Jarrett said the “hot” side of the spectrum is where NIMBYism comes from—the not-in-my-backyard reactions that push against ideas for change. However, Jarrett said NIMBYism isn’t something that should be ignored — rather, it should always be negotiated with, because the NIMBY instinct is ultimately about people’s sense of home. The NIMBY feeling is a very powerful personal instinct that is not rational and not even a human instinct: to illustrate, Jarrett told the story of an Australian magpie that instinctively attacks cyclists that may be riding too close to the magpie’s perceived sense of home.)

The elements of practicality and vision need to be in balance for optimal solutions. Jarrett illustrated the pitfalls of not balancing them:

Practicality without vision becomes habit. This is a situation where there’s too much how and not enough why. The hard rules of geometry begin to colonize your culture — two examples were the U.S. Highway Engineering service that built the interstate system (Jarrett said some describe this as the best example of Soviet central planning ever), and conventional bus operators. If an organization rewards you for doing the same thing every day, it selects against creativity. There’s nothing wrong with that, but a system biased to practicality might sometimes need a push to do things better or differently. You’ll hear statements from these organizations like “We followed the manual” — the response to that is “What values does the manual uphold?”

Vision without practicality creates boondoggles. Excitement dominating over practical concerns can create disappointing results. Jarrett’s examples of this included the Seattle monorail and personal rapid transit systems, and said we likely all knew of others. Another example he gave was a quote singing the praises of slow transit — people watching, sightseeing, etc. It’s a fine idea, but taking the concept of slow transit and implementing them as a real world project would not make any sense.

Jarrett said that emotionally intense visions imagine a finished future but not a credible path from there to there, technically or culturally. For example, some people envision strongly a world where people are less stressed and work at a slower pace—but you can’t slow transit down just to make people less stressed. For a future vision to really work, it has to be like the evolution of lifeforms: there are intermediate steps from bacteria to human, but each step in that series are still lifeforms in themselves. So it goes for transit planning: to achieve that huge future vision, your intermediate steps also have to be functional.

He gave the example of Arcosanti in Arizona as missing a bunch of steps in the middle — it’s a huge project built to create an idealized town in Arizona, but it’s not developing a credible city and culture along the way, just a big set of infrastructure.

Personal rapid transit was another example of having a vision without practicality—in this case, understanding the geometry of the system. The priority of personal rapid transit is “I won’t have to sit in a car with other strangers”—largely a cultural issue—but it doesn’t really work unless you have an enormous comprehensive network that helps people get where they need to be.

As well, Jarrett said that vision-oriented thinking often focuses on vehicles rather than the service they provide. He asked if the concept of vehicle love was an escape from the present — the most enthusiastic claims for vehicles are either futuristic or nostalgic in nature, and the present success of the streetcar could be attributed to the fact that it is both futuristic and nostalgic.

Anyway, to wrap up this part of the discussion, Jarrett said that:

- when practicality reigns, you get bureaucratic habit that’s stuck in the present

- when vision reigns, you get exciting urbanist thought that’s stuck in the future

- we need more voices in the middle, balancing practicality and vision, to have better outcomes

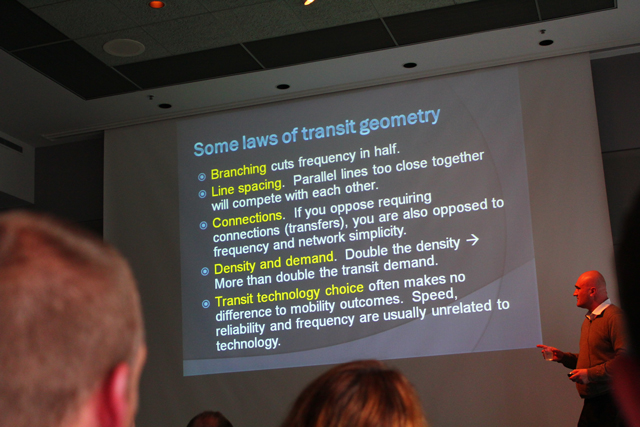

For better outcomes, respect the universality of transit geometry

Jarrett advised to respect the basic laws of transit geometry to achieve better outcomes for everyone. Often, we can use emotion to try to steamroll through solutions that are not successful according to transit geometry, but ultimately those systems just won’t work as well as they could. Some of the specific laws are shown in the photograph above: Jarrett called them “cold boring sexless facts of transit geometry.”

He ran through some examples of each of the laws then. The first law was that branching a line cuts frequency in half. Branching was exemplified by BART in San Francisco, who extended their train service to serve San Francisco airport and Millbrae — but they had to branch lines to hit the airport and Millbrae, which cut the frequency in half and didn’t serve Millbrae nearly as well. (A diagram is really needed for this one — I didn’t capture it well!)

The linespacing law stated that parallel lines too close together will compete with each other. The linespacing example focused on an area in San Francisco where three separate transit services serve three parallel streets each about a block apart. They are essentially competing with each other — removal of one would not affect the flow on the routes, and would free up excess buses to be used elsewhere, but no one has been able to consolidate the service.

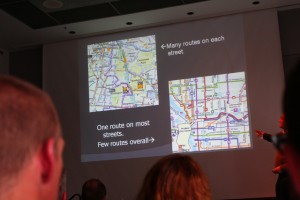

The connections law stated that transferring is inseparable from frequency and simplicity — or put another way, if you don’t want a system with transfers, you are automatically voting against a system that is simple and frequent. Jarrett’s connections principle was illustrated by two comparison transit maps — one from Sydney and one from Portland. Have a look at the picture to the right to see what I’m talking about. The Sydney map was quite complex with multiple routes on the same corridors — the Portland map was much simpler to understand, with one line along each corridor. The Sydney system tried to have long bus routes without transfers while the Portland system required you to transfer, and the outcome in Portland was a simple network where it is easy to know spontaneously how to get from one spot to another location—essentially the feeling of “freedom.” (There’s a Human Transit post that talks more about the transfer “penalty”.)

So a key question after all this was “What if we listen to geometry first?” It would give everyone a common framework to make decisions from.

And Jarrett’s final recommendation to everyone was “When you hear a claim, where is the authority for that claim coming from?” Make sure a “hot” idea works with the “coldest” facts, because once the “hot” feelings subside, all you are left with is the cold facts of the transit geometry.

Questions

Then it was question time!

Question: Why do you get more than double the demand if you double density?

Jarrett said to imagine two towns: Sparseville and Denseville. Denseville is 2x the density of Sparseville. Now pretend they have the same constant level of service — say the same bus route runs through both towns at the same frequency. Well, within walking distance of the line, Denseville already has 2x the density of Sparseville. And a more dense place will have many activities in town that encourage more transit demand—less parking on the streets, etc. So essentially, as cities get denser, there will arise more independent factors that will drive higher demand for transit.

Question: You recently wrote about Paris and wrote about their bus system. Are Paris’s bus-only lanes practical in the city of Vancouver?

First Jarrett said never to miss the bus system in Paris—it’s fantastic, and it’s all developed in the last 20 years. The amazing thing, he said, was that bus lanes were all taken from existing parking or car lanes—imagine the battle! The only difference between Paris and other cities was that Paris’s mayor simply said “We’re doing this, and we’re doing this all over the city all at once.” So yes, you can do it, if you decide to. Jarrett also mentioned that when anyone in a 1-3 million person city near a coast asks for examples of good transit, he always says Vancouver. The same issues are here but with a path to progress not found anywhere else.

Question: How do we create an incremental achievable path to our transportation goals based on cold hard facts? For example, we’re looking to make big GHG reductions in our region, but we don’t evaluate our transport plans related to this — we’re currently looking at no new transport improvements.

Jarrett said our region is always talking about our own history of sudden, dramatic change, such as our travel behaviour around the Olympics. Maybe we can just do this every day: our leaders can find another reason to ask us to travel like it was the Olympics. Also, don’t worry solely about funding. Then he gave an example of the Broadway corridor related to this question and reaching back to the question before. Suppose we find out how many people travel along Broadway in buses. Then how many travel in cars. Then, say your goal is to triple the number riding buses. Do it, and then measure how many people are riding through buses there—if it’s 50% of the corridor’s travelling population, they should get 50% of the street. Make sure the division of space is fair, and as we split up the system, there is financial benefit to all (less cars on the road, efficient utilization of transit, etc.)

Question. What are your thoughts on giving transit authorities land use planning and real estate functions?

Well this is something called value capture. Transit agencies share interest in density because it drives their ridership. The problem is the issues arising from being a developer and a land use planner. Ultimately, the issues aren’t really organizational: the issue is “are you working off the same plan?”

Question: There is a U-Pass program coming province-wide, but I go to a school that has a campus in a rural area. We’re trying to sell transit to people who have to walk about a kilometre to the bus stop, and I’m worried about the negative impact if students don’t buy in. So the walking distance to the nearest route: what kind of problem is this—psychological, cultural, etc?

This is a geometry problem. The circle of density around the stop determines the potential market. If you choose to locate a campus rurally, you simply will not have high quality transit. There’s no fighting it.

Question: What are your thoughts on an authority planning both transit and roads?

Again, the organization of the bodies doesn’t really matter, as long as the plan they are all working from is consistent.

Question: Faregates are planned for our system. There’s a debate over security versus spending a large amount of money to protect a much smaller amount. What are your thoughts?

Fare evasion belongs to the “psychology” part of the spectrum. Money doesn’t matter here, it’s all about perception. It’s also hard to measure. And if you’re trying to measure an absence, you can’t compete with someone’s hunch that the system is being cheated. We’re still looking up to Europe so here is an example. In France, all the new train stations have faregates. In Germany, all their new train stations don’t have faregates. They’ve reached this decision independently of each other and have good reasons for choosing their method. It’s a cultural and psychological thing, and a genuinely difficult concept with no clear answers. So there are political answers.

Question: When property taxes are paid to transportation from the entire region, the low density areas say “Wait, we’re not getting enough transit even though we’re paying a lot.” How do you respond to this situation?

Jarrett laughed and said his job was to describe a choice and not make it. He said that if ridership is your main objective, then that’s what you do—serve the high density areas with a lot of service, and don’t do much in low density areas. However, transit agencies have two contradictory goals — one is trying to meet a severity of need and serve those who need transit most, and the second is trying to compete for ridership. His question for transit agencies is “What’s the ridership in the places where you are actually trying to get ridership?” Because a low-ridership service with lots of empty buses often hasn’t been installed with the goal of getting high ridership in the first place.

But when he hears statements like the South of Fraser has the same population as Vancouver — this is not the same thing because the density is not the same. It balances out because you spend more on roads in low density areas, while you spend more on transit in high density areas.

Question: Can you comment on private organizations planning transit vs public organizations?

They all have their strengths and weaknesses, but it’s all about how people choose to work together or not. Service planning is intimately connected to scheduling, who is intimately connected to operations management. They must work closely together, but they don’t have to be in the same agency. Sometimes there’s very good reasons not to have them in the same agency. For example, with TransLink’s structure, maybe it’s good to have an organization that’s just about planning. In a conventional transit agency, planning can become an ivory tower while 95% of the thinking in the organization is dominated by the operations staff. There’s lots of different ways to organize, but it’s a matter of having a common plan and building relationships.

Question: Paris has a great bike system. Does it really work or is it a nice idea?

As a transit planner, Jarrett was aware that bike sharing can be important for access to transit. But from what he’s heard, it’s a success if you talk to the system’s supporters, and a failure if you talk to detractors. Jarrett’s reaction is that innovation about transportation is going on in Paris and he thinks that’s great. If someone wants to start bikesharing here, more power to them.

Question: Fare pricing. What about systems where the fare is free?

The free fare movement works in places with less than 100,000 people and a university. If something like the U-Pass comes in, the university is basically subsidizing the entire transit system, so you might as well just get rid of fares.

I think there is one valid answer to this issue and that is we have to think about what we pay for other modes and make sure we are contributing an equivalent for transit. Then he referred to the fare thought experiment posted on Human Transit for more on this.

Question: Why not spend money to extend SkyTrain to Langley?

There’s a lot of people in Langley, very good people. But density, not population, drives demand. The size of the population doesn’t matter, it’s where they are located. If you’re willing to build towers next to stations, then you are ready. But speaking just of density, Broadway in Vancouver is probably ready right now.

Question: What does Sydney do better than Vancouver?

It’s a matter of taste, but the weather is better in Sydney than Vancouver. (Lots of laughs!)

Question: There’s a movement to bring an interurban back to Chilliwack. What are the pros and cons of this? What about the construction of RAV with all the contentions around cut and cover? How does the spectrum work with this?

The spectrum frames the question, it doesn’t answer it. What I can say is that cut and cover is cheaper than boring a tunnel. And that boring a tunnel means you will have deep stations. That can make accessibility hard. In Moscow’s subway, it’s very deep and you often run into a down escalator that is disappearing off into nowhere, and you don’t know where it’s going!

To the other question about Chilliwack: TriMet in Portland had a really unsuccesful rail line from an outer suburb to an inner suburb. It didn’t go into the inner city. It wasn’t dense enough to generate demand. If you want a successful service it has to go somewhere that it’s really hard to drive to and has the density to support it.

Question: The SkyTrain is at capacity. What can we do?

As far as Jarrett knew the SkyTrain is not at capacity. But the completion of the SkyTrain line can help. The current design forces some people to go downtown even though they don’t actually want to go there. Say you do SkyTrain to Langly, you’ll start seeing the overlap of different movements — Langley to New Westminster, and so on.

Question: Can you talk more about the gap in the SkyTrain network?

He doesn’t often recommend projects–he usually just offers pros and cons and lets someone else decide–but Jarrett thinks that VCC-Clark and Canada Line have an obvious gap. Once the Evergreen Line is complete there will be lots of trains going to VCC-Clark, but what are all those people going to do there? Somehow the Millennium Line needs to reach Canada Line, somewhere in south False Creek, and this will help relieve some of the capacity. (Here’s a related post on Human Transit.)

Question: Person wanted to say that Langley has density second to downtown Vancouver, that people are on 20% of the land in that area even though significant agricultural reserves are around.

Jarrett said he hadn’t thrown out any density statistics because they depend on zone aggregates and that can be tricky to measure (if a park is near dense towers, that can be measured as low density). So that’s why he says towers are the kind of density needed to extend SkyTrain. The density needs to be right at the station to be optimal too: it’s better than having them slightly further away. So just visualize towers, and if your city is ready for that, they’re ready for SkyTrain. Also, don’t just think about SkyTrain — there are many transit products and you’ll get there faster (in many senses of the word) if you focus on speed, reliability, and frequency, and not mode.

Question: Why does Europe have better transit? Is it social marketing, policy, etc?

An interesting question! This would have a different answer in the U.S. than it does here. Canada has its own space and we can think about it in our own way — there’s a lot less federal bureaucracy telling you what to do like in the U.S.

In Europe, the older cities are better off transit-wise. The size of a city in 1945 indicates how well their transit-oriented-development has gone, although it was just called development back then. But Europe has lots of cars and freeways too. You can live the freeway life there. In Berne, Switzerland, there’s a convention centre on the freeway and you can only get there by car. But France will always treat Paris as a municipal expression of their country’s identity. There’s lots of new cities that are clever but lots are not as well developed for transportation. There are lots of examples either way.

Question: We have high density residences but not a lot of high density employment: any comments?

In business parks, especially where the nature of work doesn’t require that space (warehouse facilities will always need that low density space): you have essentially condemned those workers to driving. The suburban business park is a direct assault on civilization. It’s a fact of geometry. You can’t get high quality transit service to business parks, service that is both frequent and direct, because it is low density. Jarrett says he is not telling people that they can’t build the way they want. They just need to know the consequences and they cannot expect good transit service out there.

Question: Broadway’s Olympic express lanes — could we do that here and have them in the centre lanes?

Bus lanes in the centre lanes would not stop as often. A median busway would mean you can’t do trolleys and express buses, because the B-Lines would want to pass the trolleys. To build this you would have fast service with fewer stops, but people will walk farther to use services like that. You may want to follow what’s happening in L.A. as they’re putting in a number of rapid bus services there.

Side note: in North America, why do we think that the standard bus product is a bus stopping every 2-3 blocks and a premium product is one stopping every kilometre? What if that were reversed? We’d have a very different transit system.

Question: What are your thoughts on road pricing? How can it change transportation?

This is not in Jarrett’s area of expertise–he said he simplifies things so people can understand them. But if you’re in congestion it’s the same situation as if you give 500 concert tickets to the first 500 people who show up. There will be people waiting hours before — they’re willing to pay in time instead of money. So to this extent, with road pricing you can make them pay with money instead of time to avoid congestion.

That’s it!

And so the evening drew to a close! Those are my notes: let me know if you spot any inaccuracies and I will clean them right up.

If you want to know more about Jarrett, check out Human Transit, or try my interview with him for I Love Transit Week, and my notes from his talk on Tuesday!

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Jonathan Strang and iSkytrain, Breaking News in Van. Breaking News in Van said: A field guide to transit debates: notes from Jarrett Walker’s talk, Wed Aug 4 http://ff.im/-oMSHI […]

Thanks for your efforts in sharing the info.

Thanks for the summary!!

It was an excellent talk and really made me look at future transit projects in a different light. I’d really like to see a frequent travel map of Translink’s network.

The other excellent suggestion to come out of Jarrett’s talk was to put bus-only lanes on Broadway.

My biggest disappointment with our transit system is “THE GAP” that Jarret talks about. The Millennium Line MUST be extended ASAP to meet the Canada Line. Not with another technology – the EXISTING train line needs to be extended.

Thanks, Jhenifer, for sharing this information. This is exactly what I was asking for.

Oops. I meant to say that what he suggests is exactly what I want in Translink.

Cool blog…

[…]while the sites we link to below are completely unrelated to ours, we think they are worth a read, so have a look[…]…

[…] and table of contents, it’s available on the Human Transit blog. Also, here’s a blog post that touches on some of the subject matter in the book. Jarrett tells me the book will come in […]