SkyTrain at 40: a region shaped by transportation

SkyTrain at 40: a region shaped by transportation

When you think of Metro Vancouver, you think of the iconic seaside parks, sushi, craft beer, and the SkyTrain.

An innovation in the world of metros, the dismantling of the streetcar network, the protests against downtown highway construction in Vancouver, and the growing congestion from personal vehicles created the conditions from which the SkyTrain came to life.

With the launch of the SeaBus in the 1970s, the public sentiment was behind a revolutionary idea to build a rapid transit network that was modern, fast and automated.

The Urban Transit Authority was conscious of growth throughout the Vancouver region. Detailed LRT planning and engineering began in the early 1980s when Vancouver announced it would host Expo 86, the world’s fair, with a transportation theme. Expo required a transit system to link its two sites, two kilometres apart on opposite sides of downtown Vancouver. The announcement immediately accelerated the demand for a rapid transit system.

The designs of the network

Perhaps the biggest decision to be made in determining the features of SkyTrain was whether to make the system completely automated, including a self-service ticket system. Appraisals were made of 18 computer-driven systems and most had an attendant in the front of the cab. A survey showed that the public was more interested in safety and reliability than whether there was a driver.

BC Transit and UTDC designers worked together and created a rapid transit system that could expand easily to handle future passenger requirements. The initial capacity would be 100,000 riders a day. The long-range capacity is up to 300,000 riders per day (up to 30,000 riders per peak hour direction), using longer trains that match the 80-metre platform length, like our new MKV trains.

The early demonstrations

To provide a public demonstration of ALRT, a pre-build project was built in 1982. This included what is now Main Street – Science World Station and 1100 metres of track. A two-car prototype demonstration train operated from June to November 1983 giving rides to the public.

More than 300,000 people visited the project and accompanying information exhibition. A survey showed that 80 per cent of visitors conditionally or unconditionally supported the rapid transit concept.

Connecting the downtown core

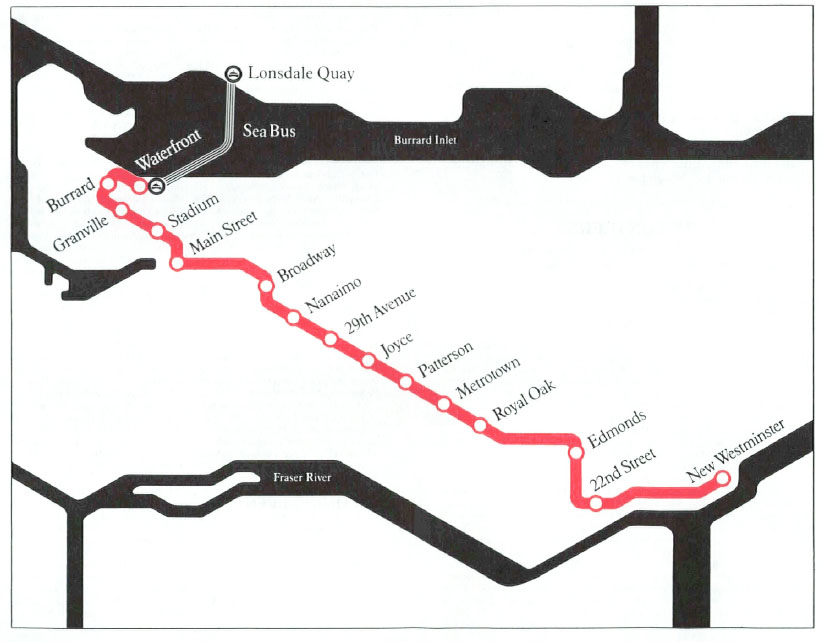

The first phase of the rapid transit route stretched from the Vancouver waterfront and downtown through Burnaby to New Westminster and included 15 stations. The SkyTrain alignment largely follows the old British Columbia Electric Railway line, which ceased operations in 1955.

The most difficult location and construction was in downtown Vancouver, a maze of modern office and commercial towers. The existence of an old, single-track conventional railway tunnel that followed close to the ideal alignment eliminated the need to consider elevated, at-grade, or cut-and-cover tunneling. It avoided digging up the city centre and saved an estimated $100 million.

The most difficult location and construction was in downtown Vancouver, a maze of modern office and commercial towers. The existence of an old, single-track conventional railway tunnel that followed close to the ideal alignment eliminated the need to consider elevated, at-grade, or cut-and-cover tunneling. It avoided digging up the city centre and saved an estimated $100 million.

Built in 1930, the Dunsmuir tunnel was designed to link two railway yards – False Creek and Burrard Inlet – and was now reimagined for a modern era of transit.

Crews excavated and rebuilt the tunnel’s bottom, which allowed the guideway to be tiered for stacked train operation. They restored the structural integrity of the old tunnel by injecting grout into gaps behind the lining.

The building of two underground stations, Burrard and Granville, was one of the most difficult contracts of the entire system. It comprised the enlargement of the existing tunnel to accommodate station platforms, construction of station tunnels and shafts. Work, particularly blasting, was made difficult by the close proximity of foundations of neighbouring high-rise buildings.

One interesting exercise in the tunnel design occurs near Stadium Station, where crews built a new section of tunnel in a semi-spiral design to transition the stacked guideway configuration to a side-by- side configuration in Stadium Station.

For design and construction purposes, the project team divided the project into 12 geographical sections. They awarded more than 60 major construction contracts in total. The largest single contract, which they awarded to Supercrete, provided the supply of guideway beams. This contract, valued at over $50 million, represented the biggest contract of its kind at the time.

Arriving to a world stage

SkyTrain was a success from its first opening.

During eight “free-ride” days, people flocked from far and wide to ride. People filled the trains to beyond design capacity, eager to try out the new system. Crowds formed lineups, sometimes three blocks long at some stations.

During these special days, starting on Dec. 11, 1985, the service carried 60,000 people during a nine-hour day. Rapid Transit staff and train controllers gained valuable experience.

On Jan. 3, 1986, SkyTrain went into revenue service providing four-car trains every four minutes during rush-hour and every five minutes during off-peak hours. Service was an ambitious 19 hours a day, Mondays through Saturdays, and a limited six-hour service on Sundays.

From Day One, ridership figures quickly overtook projections. During the first week SkyTrain handled 40,000 a day during the week, and by the end of the first month this had risen to 50,000 a day. The major surprise came on Saturdays. Most transit operations experience a drop in Saturday ridership: SkyTrain not only maintained weekday averages but jumped to a steady 70,000 on Saturdays.

Within three weeks, SkyTrain had recorded its first million passengers, carrying 45-50,000 passengers on weekdays, considerably higher than the projected figure of 40,000.

As part of Expo ’86, many special guests rode the SkyTrain, including Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Premier Bill Bennett, their Royal Highnesses Prince Charles and Princess Diana, and Mickey Mouse, whose iconic monorail at Walt Disney World suddenly seemed outdated.

Of 22 million Expo ’86 visitors, most rode the SkyTrain, travelling between the fairgrounds and exploring the region beyond downtown.

The first stretch of the Expo Line not only connected downtown Vancouver to New Westminster, but it also fundamentally changed how the region developed, mirroring the urban growth seen a century earlier along the interurban lines.

Connecting today, tomorrow, and the future

Today, the SkyTrain system, which started as a single line, has grown to become one of the longest fully automated rapid transit network in the world. It carries hundreds of thousands of riders daily, connecting them to the people and places that matter most.

As we celebrate 40 years of service, our focus is already on the next chapter. We are preparing to launch even more ambitious projects, including the Broadway Subway Project, which will extend the Millennium Line, and the Surrey–Langley SkyTrain extension of the Expo Line, connecting communities south of the Fraser River.

Like the electric streetcar and the interurban before it, the SkyTrain is more than just transportation; it is the physical thread that weaves our communities together.

Here’s to another 40 years of connecting Metro Vancouver!

Alex Jackson

Their Royal Highnesses King Charles and Princess Diana disembarked at “Patterson” SkyTrain station.

Happy 40th Expo Line!

I love U, SkyTrain!