The Central Park Line: the very first interurban in greater Vancouver

The Central Park Line: the very first interurban in greater Vancouver

Today, I’m pleased to present a brief look at the Central Park Line, one of the interurban lines that used to run in the Lower Mainland.

(If you’re not familiar with the interurbans – electric railways that ran between cities – you can check out this earlier blog post on the history of the interurbans in greater Vancouver.)

Again, Lisa Codd, the curator at the Burnaby Village Museum, helped me put this article together. It’s a continued collaboration to explore transit history and Burnaby’s archival holdings!

About the Central Park Line

From 1891 to 1954, the Central Park Line ran between New Westminster and Vancouver.

It’s probably a familiar route for many of you: much of it is the same route as the current Expo Line, from Broadway to New Westminster Stations.

In 1986, SkyTrain was actually built along the exact corridor that was previously used for the Central Park Line through Burnaby. The transit corridor had remained empty for those years, so it was a perfect spot to install the new rapid transit service.

The conductor and motorman: the men operating the interurbans

Two men worked on an interurban tram: a motorman would drive the interurban, and the conductor would collect fares and help the customers.

The conductors and motormen would communicate with each other via bells on a cord. When a passenger requested a stop, the conductor had a particular code he rang to let the motorman know. The conductor would also let the motorman know when they were clear to leave the station.

Every interurban had two motorman’s vestibules: one at each end of the tram. When the tram reached the end of the line, the motorman would move to the other vestibule, and the tram would head back in the opposite direction. He would take down the trolley pole and put up a second pole that faced in the opposite direction, and take his motorman’s stool to the other end.

When two or more cars were hooked together, there could be additional conductors and/or a brakeman added. But brakemen mainly worked on the freight runs, as they were needed to help get the trains off the track and onto sidings.

Generally, the passenger service interurbans generally operated with a motorman and conductor only. The streetcars eventually went to one-man operations, but the interurbans remained two-man operations.

By the way, both conductors and motormen wore navy blue suits. The BCER issued hats and brass “BCER” buttons that they would sew onto their suits, which they purchased themselves.

Stations and stops on the Central Park Line

How many stations were on the Central Park Line?

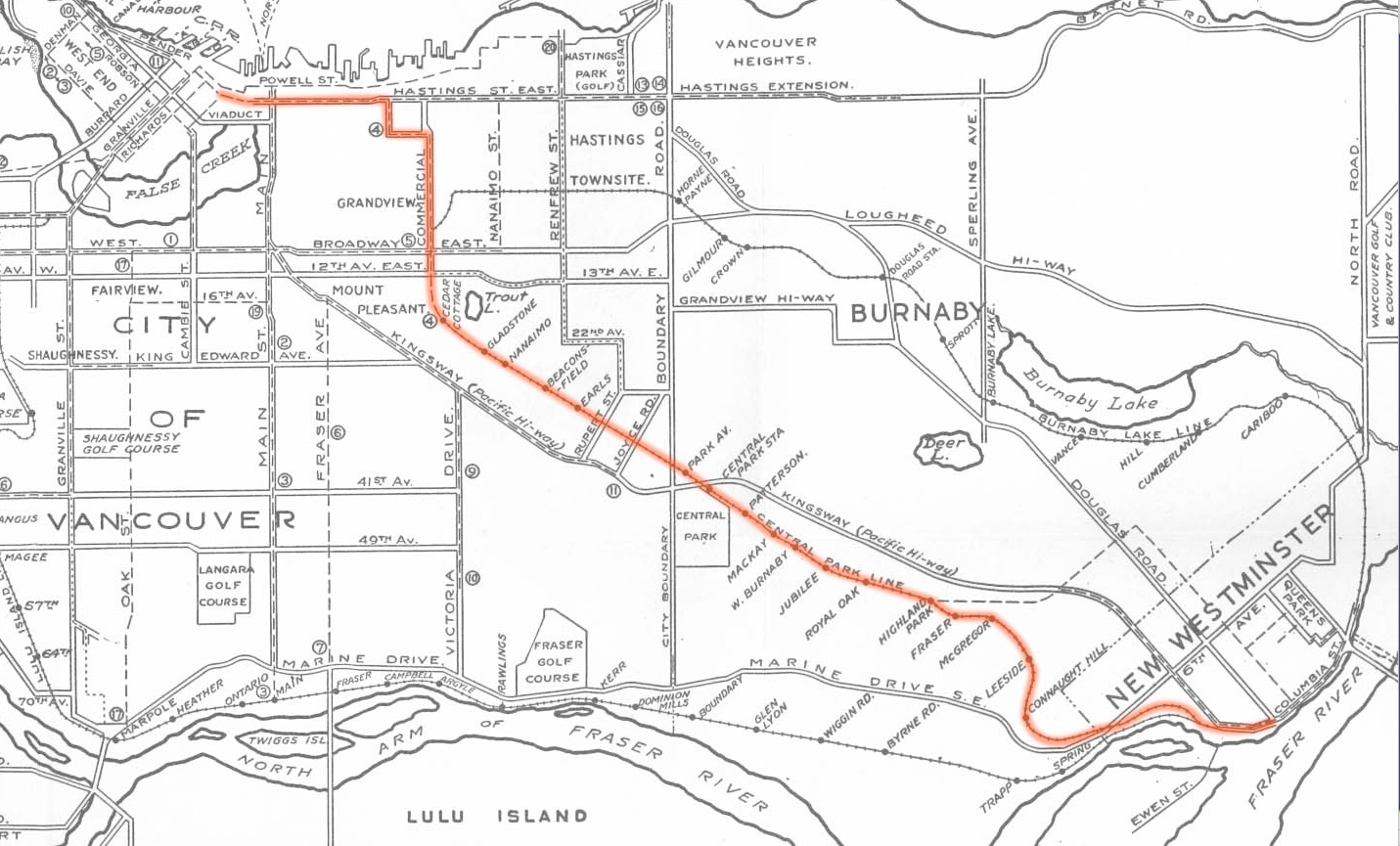

Well, the Central Park line grew over the years, so the number of stations varied. But the 1936 transit map published at the start of this post shows the line at its peak, with 16 stations.

However, from the downtown Vancouver depot at Carrall to Cedar Cottage (right by Trout Lake), the Central Park interurban functioned more like a streetcar, stopping on the street to pick up passengers. It was the same thing on the other end, when the line got into New Westminster.

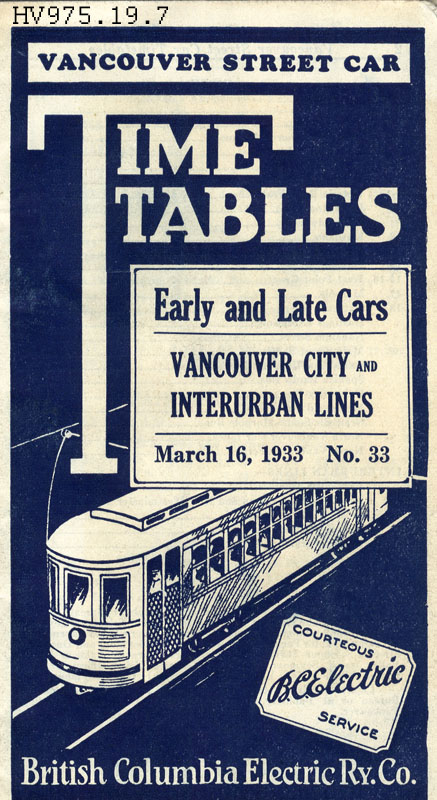

Also, here is a page from a 1933 streetcar and interurban scheduling book, if you’re curious about the timing of the line.

Between Cedar Cottage and the Connaught Hill Station, there were actual stations with buildings.

Here’s a picture of Edmonds Station circa 1912 — a man is changing the car tire in front of the station. These were standard station designs, and were used throughout the route, including the Fraser Valley.

At some point in the 1930s/1940s, the stations were renovated, probably to make upkeep easier.

The Museum’s Vorce Station (which was on the Burnaby Lake Line) is an example of a station that was altered—here’s a picture showing what it looked like in the 1940s.

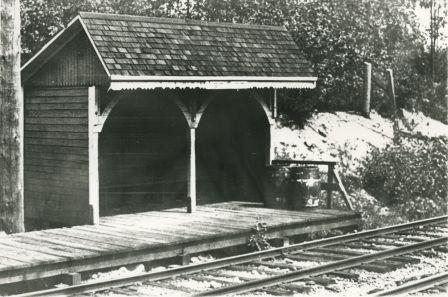

However, there were also simpler stations, like Leeside station on the Central Park Line, shown at right.

This photo comes with a delightful caption too: “Reuben Butcher (father of Violet Butcher Lynds) walked to here to catch the tram to work at B.C. Sugar in Vancouver. Lanterns used by passengers walking to and from the station during dark winter mornings and evenings were left under the wooden floor of the station.”

Some stations were also larger. The Highland Park station was a bit of a hub, serving as a transfer point to the streetcar that operated in the neighbourhood. The station included a convenience store called the “Dinky Store” owned by Burnaby’s Thould family.

Here’s the caption for this photograph: “Photograph of the “dinky” store (so-called because of its small size) at Highland Park Interurban station at Buller Avenue. In front: Margaret Thould. Lionel Thould, who opened this store, later opened a similar store at Fraser Arm Interurban station and gave up the Highland Park store when buses replaced first street cars, then Interurban trams.”

Impact on Burnaby development

As we are well aware of today, development of a public transportation line can spur city growth and shape its business development.

The Central Park Line is a great example of this—development of the interurban line between Vancouver and New Westminster had a great impact on Burnaby and the line’s two anchor cities.

When the line was originally built in 1891, the area between New Westminster and Vancouver was unincorporated. The development of the railway led to the incorporation of the Municipality of Burnaby in 1892.

Gaslights to Gigawatts, the history book produced by the B.C. Hydro Power Pioneers, also gives a great overview of exactly how B.C. Electric and the rail line prodded this development forward.

For example, B.C. Electric worked with real estate companies to encourage homeowners and businesses to locate themselves along the new line.

The company even made special offers to encourage people to move: for instance, free transportation passes for a year, industrial rates on freight and power, and cheap land.

And the railroad’s freight transport kept the company profitable and the people of Burnaby and New Westminster in business. Settlers could use the railroad to send their eggs, chickens, and market crops for sale in the cities. Bricks from New Westminster and cord wood and shingle bolts from Burnaby were also transported via rail to Vancouver.

There’s also a great fun fact from the book: “The company added a Strawberry Special in 1903 just to move the fruit crop”!

Electricity!

The interurban line also helped bring electricity to Burnaby, powering the tram lines and the city.

And in fact, the first Council of the new municipality of Burnaby met at the boarding house that served as the home for workers at the nearby powerhouse that operated the electric railway.

The BCER built substations like the one at right, carrying in power from the BCER’s Buntzen Lake power dam.

For this substation, electric lines came across the inlet at Barnet, along the Barnet-Hastings Road to Sperling Avenue (which was built for this project and originally called Pole Line Road), and then south to this site at the corner of Griffiths and the Central Park line.

This brick substation replaced a wood-fed steam powered substation, and converted alternating current from the Buntzen power plant to direct current for the operation of the Central Park route.

Originally known as the Burnaby Substation, it eventually became known as the Newell Substation. The original brick building was replaced by a new structure in 1930, which was demolished in the 1960s in favour of the open field substation that continues to operate on the same site at 7260 Griffiths Avenue.

The end of the line

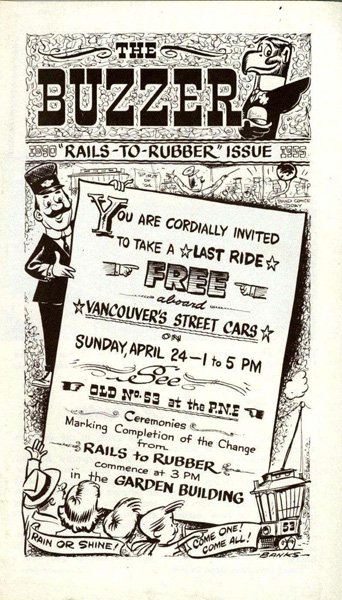

The Central Park Line made its final run on July 16, 1954.

As explained in the previous blog post, the B.C. Electric Railway Company – the private company who ran transit at the time – made a decision in the 1940s to switch to buses and dismantle the streetcar and interurban system.

The Company realized that with no expensive permanent tracks to install and maintain, motorized transport was the way of the future.

And so ended the Central Park Line, though its route is still alive through the SkyTrain!

Want more history?

Thank you again to curator Lisa Codd for all her help with this article!

You can find all of the historic images in this article and more at the Heritage Burnaby website. This comprehensive resource brings the City of Burnaby’s archival documents, photographs, museum artifacts, and heritage landmarks under one virtual roof for easy public access.

And of course, visit the Burnaby Village Museum for more history treats! Again, it’s is an open-air museum that recreates life in 1920s Burnaby. It’s open until September 7 for the summer season this year. (Check the museum’s website for admission costs and more!)

For more on local transit history, take a look at the books of Henry Ewert – he’s a local historian who has written books such as The Story of the B.C. Electric Railway, Vancouver’s Glory Years: Public Transit, 1890-1915, Victoria’s Streetcar Era, and The Perfect Little Street Car System: From Ferry to Mountain in North Vancouver, 1906-1947.

You can also try TRAMS, the Transit Museum Society, who run a real-life restored streetcar on the Downtown Historic Railway. And B.C. Hydro’s Power Pioneers association runs a great history website that includes info on streetcars.

And you can’t beat Chuck Davis for more regional history – check out his website, and his terrific series in Regarding Place magazine called A Year in Five Minutes, which showcases stories from each year in Lower Mainland history.

Hope you enjoyed this look back at the interurbans!

That Buzzer issue from 1955 is so sad. If only we could turn back time and fix the future!

Noted that July 16th,1954 was the last runs for the Central Park interurban. Quote-Centennial calendar, BC Transit, 100 Years.

There’s a great DVD you can borrow from VPL called “B.C.E.R.: Then and Now”, put out by TRAMS, consisting of 2 hours of nothing but original 16mm film footage from the early 1950’s, shot while riding on everyday streetcar & interurban trips around Greater Vancouver. The audio is of former operators talking about what they see as they drive down the lines and memories they have of driving streetcars & interurbans. I believe there is a section of them going down the Central Park line at one point. The video is fascinating and has stuff on it I’ve never seen anywhere else, including some very sad footage of workers burning up old streetcars under the Burrard Bridge after they were put out of service! :( All you transit historians out there should definitely check this DVD out if you haven’t already.

Cheers, great article Jhen and neat pics too! :)

[…] The Central Park Line: the very first interurban in greater Vancouver [The Buzzer Blog] Vancouver traffic puts pedestrians at risk [The Georgia Straight] Vancouver park […]

Reva: thanks for the tip! I will definitely have to check out that DVD.

Shane: get working on that flux capacitor :D

hi, I was wondering if you have a photo or a sample i can buy of the wooden tokens used on the busses when i was growing up in vancouver in the 60’s i told my wife and other people and they just don’t believe it.

Gerry:

Sorry for the delay in this response. I asked around and no one had pictures of the tokens from the 60s. As far as I have been told, the tokens were plastic, not wooden, as well. (Although I could be wrong!)

However, for a very vivid description of how the token system worked, you might be interested in this article by veteran driver Angus McIntyre. There is also a 1965 CBC video linked in that article, so perhaps give it a look and see if it shows the tokens there — I couldn’t tell!

I noticed that there are still sections of the old Interurban track scattered alongside the Expo Line. I wonder if there is any possibility of that track being reconstructed one day to provide a direct line downtown for commuter trains from south of the Fraser to supplement the load when the Expo Line reaches capacity, and Amtrak Cascades trains to the US.

Enjoyed reading about the old Central Park Line — it was our only mode of transportation into Vancouver in the 1930’s and in the 1940’s I rode to work everyday from my home in South Burnaby….good old times…thanks so much.

Thanks! This is a great Buzzer story about a truly beautiful park. I live close to Central Park and walk and jog through it all the time. As time passes I love it more and more. What a place to unwind, go see the ducks, play some pitch-and-putt, volleyball, tennis, walk, jog, picnic. Beautiful, tall trees everywhere. There is a positive spirit and energy in the park and people always seem happy to be there. PERFECT.

rituals made,past-present and future,to date

When the Skytrain was proposed and built along the Central Park alignment, was there any resistance to building the line along the corridor? Or, did the people of Vancouver in 1986 embrace the idea of reusing this right of way for this purpose?

Oq ayiq sekis iskachat bespilatno

wheelbarrow she is so excited that she was ready to rush to the poles.