Building a better transit line: how location and land use make or break good transit service

Building a better transit line: how location and land use make or break good transit service

This post is part of a series about Managing the Transit Network: all about how TransLink plans transit service in our region. See all the past blog posts in the series here.

This post covers pages 12-21 in the Managing the Transit Network primer.

So far in our series, we’ve talked about the overall goals and challenges for transit planning. And we’ve looked at the broad themes we keep in mind when we design a transit network. (We also did an interview with the planning team behind this project!)

But in this post, we’re going to take a look at transit planning on the street level. That is, how do we design a good bus route or transit line? (And by “good,” we mean “a transit line that serves lots of people for as much of the day as possible.”)

Well, there IS an actual answer. Generally, we try to design a transit line with nine specific elements to make it likely to serve lots of people almost all the time. They are:

- Serve areas of strong demand

- Have strong anchors at both ends

- Be as direct, simple, consistent and legible as possible

- Maintain speed and reliability along the entire route

- Avoid duplication or competition between transit services

- Match service levels to demand

- Have balanced loads in each direction

- Experience an even distribution of stop activity

- Have an even distribution of ridership by time of day

We’ll talk about each of these elements in more detail below. But eagle eyes will already note that locations and land use of the existing environment play a big role in making a transit line a success!

Serve areas of strong demand

Where do you build a transit route if you want it to gain high ridership quickly?

Connect the places where everyone wants to go—and your route will do especially well if those places are inconvenient to drive to.

It may sound obvious, but it’s worth spelling out to ensure everyone understands. Good transit service—service that everyone wants to use—connects the places where lots of people want or need to get to.

These places are essentially destinations of concentrated activity—like town centres, hospitals, universities, and shopping centres, or just places where many people live and work. If it’s inconvenient to drive to these destinations, even more people are likely to take transit to these areas. (For example, perhaps parking is more expensive or limited near these destinations.)

It’s worth noting that if these places have a variety of uses and buildings, a transit line has a better chance of experiencing decent ridership all day. For example, if a movie theatre is next to an office building, there are riders who will take transit to work during the daytime, but there will also be riders trying to get to the movies throughout the day and the evening too.

Have strong anchors at both ends

We make an effort to start and end our transit lines at major activity centres or connection points.

Why? Well, a transit line works best if lots of people want to get on at both ends of its route. This means the “anchor” destinations at both ends need to be places that many people want or need to go—good examples include a major bus exchange, rapid transit station, hospital, or university.

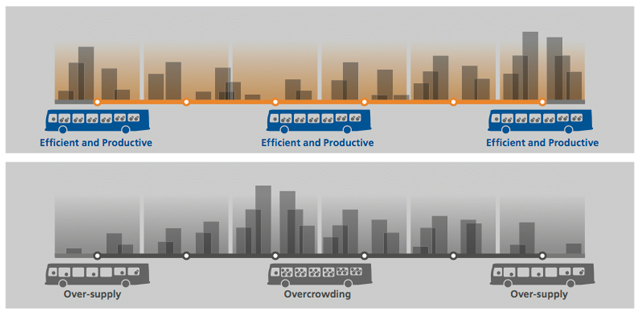

The illustration above shows why it’s important to have solid anchors at both ends of a transit line. The top diagram shows a transit line with solid anchors and destinations along the way. The line is always serving lots of people throughout its journey. Every hour that it is in service, it’s serving a good number of customers. Thus, we aren’t running empty buses at high cost which aren’t helping riders get to their destinations. We’re also not overcrowding the bus.

The second diagram shows what can happen if a line does not have strong anchors. Buses start off empty and gradually fill up. Near the middle of the route, where demand is highest, there could be overcrowding, making the ride unpleasant for our customers. Near the tail end of the route, the buses empty out again. The cost per passenger near the ends of the route is high, since we’re trying to provide enough capacity to serve the busy middle section. So for most of the time, this line is running empty buses with not enough customers, and in the middle, the bus is too overcrowded to be an attractive ride.

Be as direct, simple, consistent and legible as possible

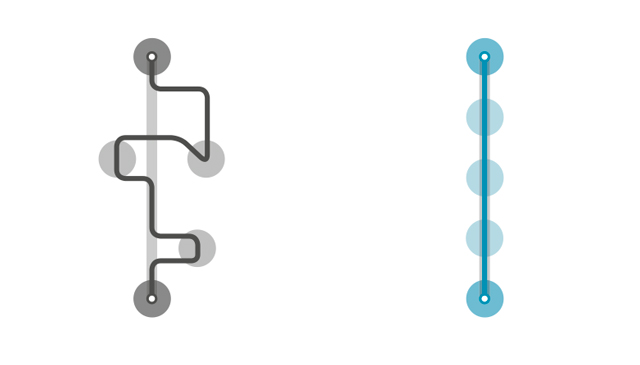

We try to make our transit lines as straight as possible.

An effective transit line will follow a reasonably direct path along most of its length—after all, the shortest way between two points is usually a straight line. It’s also more cost-effective to operate, since it requires less time to run the route.

A direct transit line is also much more appealing for riders. A transit line that meanders instead of going straight to its destinations will usually drive its riders nuts. We’ve all experienced this kind of “milk-run” transit ride, which takes forever to get to where you want to go. Lots of riders get very annoyed with this type of service.

And there’s one more benefit from making a transit line as straight as possible. It makes it more legible for people—meaning it’s much easier for riders to understand and remember where the transit line is going. That’s important, because knowing the transit system like the back of your hand helps you easily figure out how to use transit to get to where you need to be, and thus more likely to take transit.

All this benefit from straight lines!

Maintain speed and reliability along the entire route

If your transit line connects popular destinations, it still won’t attract riders if it’s slower than driving and never on time at its stops.

And from our side, a slow, inconsistent service is more expensive than a fast one. (For example, more driver time is needed to operate a slow bus route, and more fuel is wasted.)

So we try our best to create favourable conditions that ensure that our transit lines are fast enough to be a reasonable alternative to a car, and to help them stay on schedule.

One major factor in affecting speed and reliability is how many times a bus must stop. Stops happen at places like intersections and bus stops, or just on the road due to traffic congestion. And all these delays can really impact how well the whole transit line serves its riders.

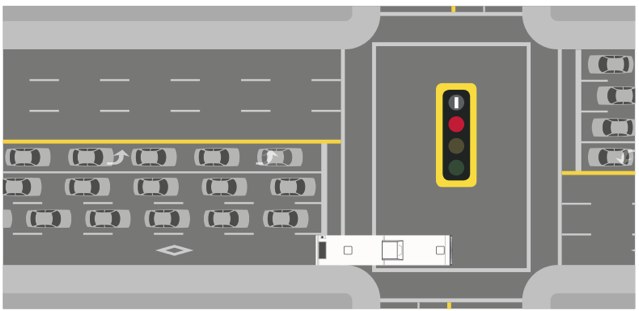

But! There can be an answer. We can use transit priority measures to help alleviate some of these delays.

As you might have guessed, transit priority measures are tactics taken to give priority to transit over any other traffic. They work on two types of transit delays: signal delay (the time buses spend waiting at lights) and congestion delay (the time lost by buses waiting in traffic). These methods include:

- bus-only or HOV lanes on congested roads

- traffic signal priority, where approaching buses cause an extended green light or shortened red light.

- transit priority signal indicators, where a special traffic light (a white vertical bar) allows buses to advance through an intersection ahead of other traffic.

- bus-only or HOV interchanges, where ramps onto highways are reserved for buses or high-occupancy vehicles.

- other measures to manage traffic in a way that improves bus operations.

We work with our municipal and provincial partners to help implement these solutions, and the outcome is usually faster, more reliable service for our riders. And at the same time, we try to discourage road changes that may hurt transit speed and reliability.

As well, where there’s lots of demand for longer faster trips, we’ll sometimes introduce B-Line or limited-stop service. Less stops means a faster, more reliable trip, which gets you to places faster, and helps us increase the frequency of our buses without adding extra cost.

Avoid duplication or competition between transit services

To build a successful transit line, don’t put it so close to other transit lines!

Routes that are too close or overlap also tend to reduce ridership on both lines, as the same population of riders will now be split between the two lines. And if routes are too close or overlap, we’re overserving one population with resources that could go to serve other places.

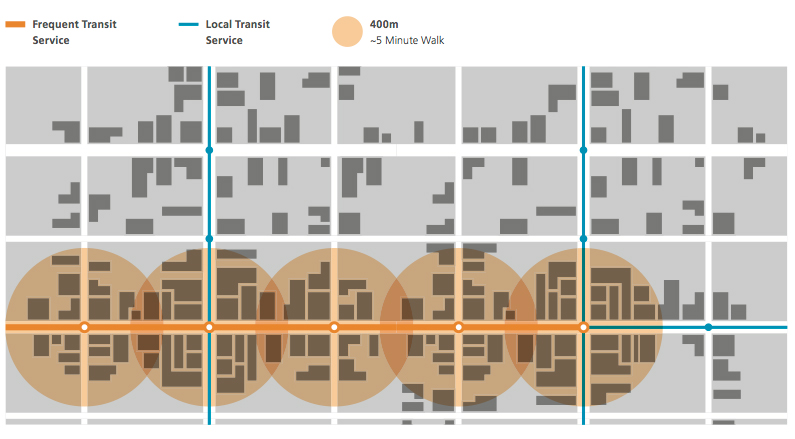

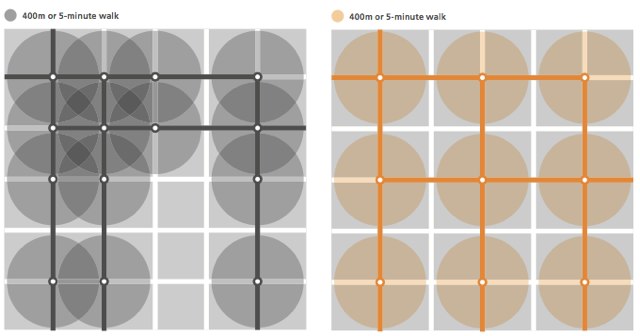

We try to space out our parallel transit corridors by about 800m, so locations in between are within walking distance to one line, but not two. (400m is considered a 5 minute walk.)

Match service levels to demand

An effective transit line provides the appropriate level of service to meet demand and encourage people to use it.

A good example is a line where buses run often during the day to help get students to school, but less often in the evenings when fewer people are expected to ride it. This service meets demand when it is greatest, but keeps costs in check by running buses only when people are riding.

So when we think about our transit network, we try to understand the differing travel demands around the region, and how we can match the service to that demand effectively. It’s important to note that we plan the entire network this way, thinking about each transit line in the context of the broader network of transit services (SkyTrain, SeaBus, Bus, etc). It isn’t buses competing against trains, but how they all work together to provide good transportation outcomes.

There are a few variables that we can adjust to affect service levels on a given transit line:

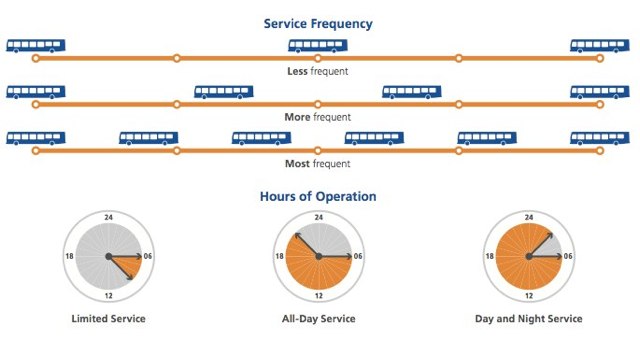

- Frequency: How often the service runs determines how long people have to wait and how easy it is to make transit connections.

- Span or duration of service: When and how long the service runs. Some services run only during the peak commute period. At the opposite extreme, some run for most of the night.

- Stopping pattern: Closely-spaced stops provide good access but lead to slow operations. Stops that are further apart lead to faster travel times. That’s why we clearly distinguish local services from Rapid or B-Line services. On some streets we offer both local and B-Line service because the stopping patterns make the lines useful for different trip purposes.

- Exclusivity of right of way: Transit priority measures, such as bus-only lanes, or transit priority signals help minimize delays to buses at intersections and along congested roads. An exclusive right of way, where a line is not affected by other traffic, is a distinct feature of SkyTrain, SeaBus, and Bus Rapid Transit. It is the best way to ensure high reliability and consistent speed.

Have balanced loads in each direction

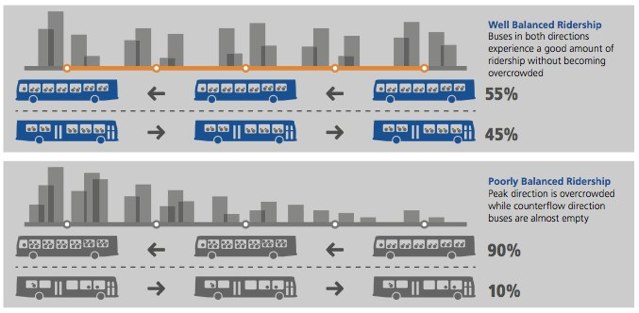

Having balanced loads in each direction on a transit line is important. It costs about the same to operate a bus that’s full of passengers as one that is driving around empty. And since we can’t run transit vehicles (and drivers) in one direction without also running them back, the capacity provided in one direction is usually the same as the other.

A balanced load means demand is about the same in both directions. That means we’re not wasting any money running empty buses on the route.

However, not all transit lines have balanced loads. A transit service might be very productive in one direction but unproductive the other way. For example, a bus line from a suburban residential community to a city centre will have a lot of passengers inbound during peak morning hours, but few passengers going the opposite way at that time. This is a problem for transit because we can’t run transit vehicles (and drivers) in one direction without also running them back.

That’s where land use comes in. If a corridor offers a variety of land uses, with many different destinations along the way and at both ends, riders will have reasons to travel in both directions. On these types of lines, transit vehicles are less likely to be crowded in only one direction and nearly empty in the other. Zoning and other land use decisions that encourage a diversity of uses can really help improve ridership and efficiency of a transit route!

Experience an even distribution of stop activity

Similar to the balanced loads point above, transit service is more productive when there are many places along a route where people want to travel.

But that only happens when land use decisions have built a place where there ARE a lot of destinations along a route, when there are lots of people living and working along the route, and when there’s a nice variety of land uses encouraging different activities along the route. And it’s also important that the environment is welcoming to walk around in as a pedestrian!

Services that are very busy at only a few stops tend to generate overcrowding—people get on, fill the transit vehicle, and nobody gets off until that one important stop is reached. Uncomfortable!

But if you have lots of people getting ond and off at a range of stops, you get the following nice benefits:

- Passenger turnover – many different passengers can use the same number of seats on a transit vehicle following the route.

- Reduction in overcrowding and pass-ups (when a transit vehicle is too full to pick up more people at a stop) – space is always becoming available as passengers get on and off at multiple stops.

- Increased fare revenue – while the cost of providing the service is constant, more people use and pay for it.

Have an even distribution of ridership by time of day

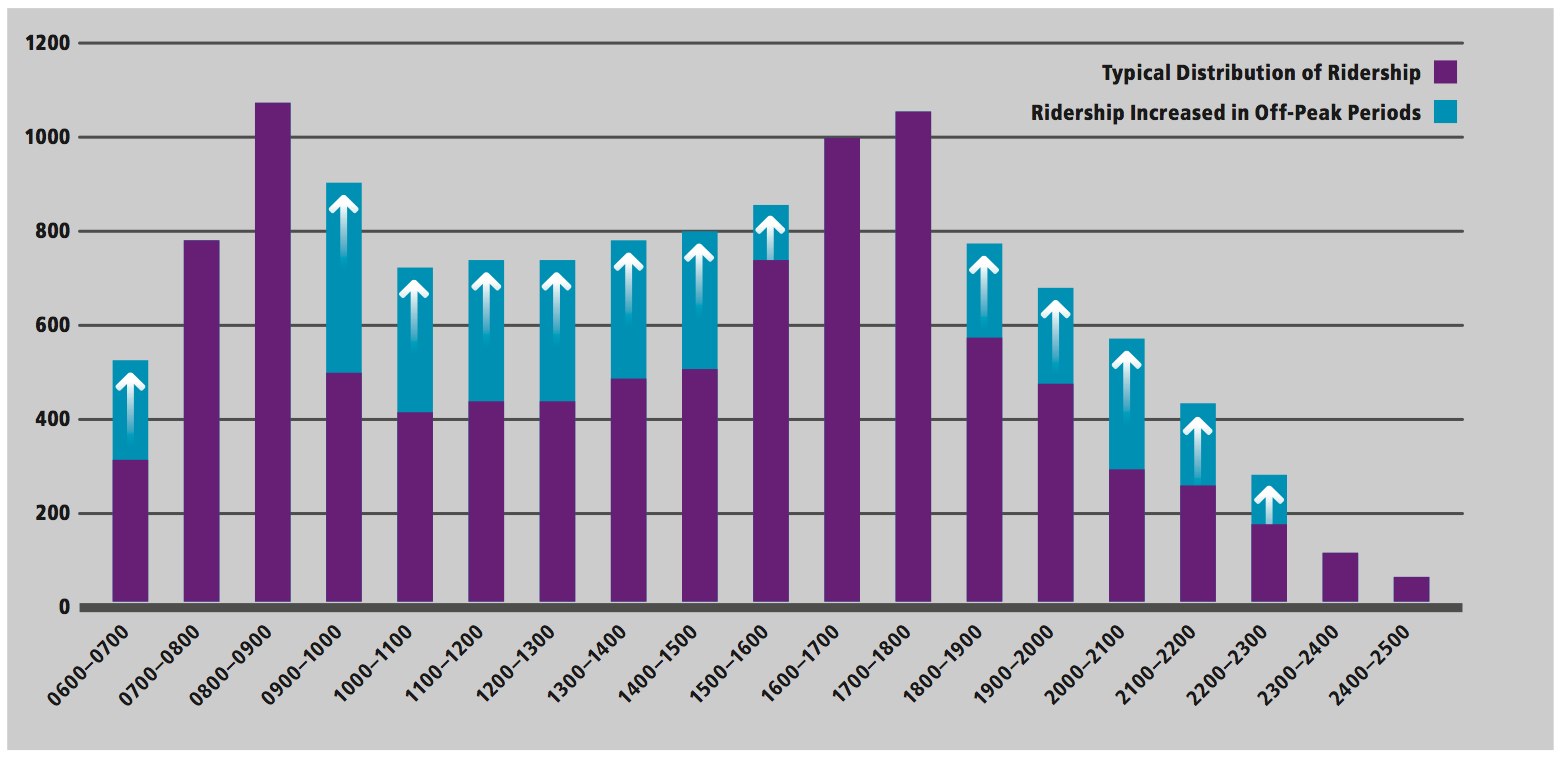

Did you know most transit trips are taken in the morning or afternoon rush hours? That’s when people are travelling to and from work or school.

This travel pattern has an impact on transit service for the rest of the day and week. It means there are fewer transit trips taken during the middle of the day, evenings or on weekends. This can lead to overcrowded buses during peak periods, and empty transit vehicles during off-peak periods. Which we try to avoid!

As we’ve talked about, an efficient transit service will have riders all day in both directions. Lines like these justify having higher levels of service throughout the day—because people are using the service!

Having riders all day is key to making transit a more viable alternative to car ownership. And it’s an important requirement for getting a corridor to Frequent Transit Network (FTN) levels of service—corridors where you can expect convenient, reliable, easy-to-use services that are frequent enough that you don’t need a schedule. (The Frequent Transit Network is an important part of our work — find out more about it!)

And again, land-use decisions that support transit ridership in the off-peak hours (usually by mixing uses) can help transit serve riders better and be more efficient. And again, it’s an ongoing partnership that we all work on.

Put your planning hat on: discussion questions

All right, now it’s your turn to play the planner! Here are the questions dreamed up by the planning team. This week’s discussion questions are framed as hypothetical situations representing some of the challenges that TransLink faces on a regular basis. Leave your answers in the comments and we’ll get you some responses too!

Scenario 1

A municipality on the edge of the region has approved a new area in their jurisdiction for development. They’ve approached TransLink, requesting transit service be provided to this new and growing neighbourhood. The development is in a remote location, removed from the existing transit network by several kilometres. It is also near the edge of Metro Vancouver’s urban containment area, near the base of a mountain and otherwise surrounded by very low density agricultural and forest land. The development is largely single use, large lot residential with some smaller lot rowhouses and townhomes. How would you, as a planner, respond to the municipality’s request for service? What type of ridership is it likely to generate? Some people have already moved to the area and are asking for transit service. What priority should TransLink give to this service versus other needs across the region?

Scenario 2

A bus route currently operating along a corridor generates relatively good ridership and provides a fairly direct connection between two urban centres. A resident has called TransLink to request the route be diverted from its normal route to stop closer to their residence. Perhaps not all trips – just a few trips in the morning and a few trips in the evening so the person can get to and from work. The detour would add about 5 minutes to the end-to-end travel time of the service (currently ~25 minutes). The person in question has gone door to door and gathered names and phone numbers from a number of their friends and neighbours supporting the request. What are some of the things a planner should consider when responding to this request?

Scenario 3

A company has chosen a new location for their head office in a business park just off a freeway. Transit does not currently serve the location. The owner of the company has called TransLink to ask for a bus route because 4-5 employees would like to use transit. The owner says that if a bus served the location even more people might use it as there are several other employers nearby. The owner has written a letter to the local mayor. Is this a good use of transit resources? How should TransLink respond? Are there other options the company could explore?

Scenario 4

A large industrial area has been established in the region. The area is growing every year as new businesses move in. People who work in the area come from all across the Metro Vancouver area and the Fraser Valley – from as far away as Chilliwack, Squamish and South Delta. Because of type of businesses in the area, work start and finish times vary throughout the day and night. The area is in a remote location, surrounded by agricultural lands and far removed from the transit network. Calls for transit service to the area are frequent and come from employees and businesses in the area as well as the local council who want to support these local businesses. What type of route is capable of serving the area if workers come from all over the region at different times of the day? How should TransLink approach the issue?

Read the rest of the series

Again, this post covers pages 12-21 in the Managing the Transit Network primer. Make sure to check out the primer and the rest of the blog posts below:

I just wanted to make a quick comment. A while ago, I tried to get all I Love Transit Nights to occur outside of Vancouver. I did that in hopes of encouraging us to see Surrey as a strong anchor. This is also why I am very excited about New Westminster building a better downtown.

I find this hilarious. For starters…

“Be as direct, simple, consistent and legible as possible”: the picture on the right (a loopy route) is what isn’t desired – yet it’s pretty much the standard route outside of Vancouver. I’ve posted a few of the more obnoxious routes like that in Burnaby, although it describes most of them.

“Avoid duplication or competition between transit services”: that describes the service in New Westminster.

*I don’t know my lefts from my rights*

I’m with Eugene on trying to have most of the I Love Transit nights to happen outside of Vancouver.

Euguene and Sheba: Jhen and I are open to different venues for I Love Transit Night. So far, we’ve had two in Vancouver (1. Commercial 3. Joyce), one in New Westminister (2.) and this year’s in Burnaby (4.). We found the community centre was a good venue this year for a number of reasons. If you have any venue suggestions in Surrey with a similar feel to Bonsor Recreation Complex in Burnaby, we’re all ears!

Hi again Sheba: I shared your first comment with our planning department who sent me the following response:

“Thanks Sheba, we definitely recognize that there are routes in the current transit network that don’t quite mesh with all of these design considerations. That’s how we know we have work to do! The existing network has evolved over many years, with various drivers influencing the design of individual lines. The design considerations articulated in the primer are really meant to guide our current and future decisions about changes to the network. We have to tread carefully when making changes to existing services though, since we know that our customers depend on them. That’s why we consult with the public before we make changes to the architecture of the network. We’re hoping to come out with some ideas in the fall for changes we can make in the near term. Some of which will likely address many of the issues that have been brought up in the buzzer blog comments about the legibility of the network in New Westminster, Burnaby and Coquitlam.”

It’s nice to see the planners paying lip service, but I think I speak for all of us that have brought up routes not even remotely following these guidelines when I say this – I’ll believe it when I see it.

TransLink took over from BC Transit in 1999. There was a reorganization in 2007. It is now 2012. That means that there has been 12 years (or 5 if you count from the reorganization) to fix up routes to bring them more in line with the elements listed above.

Please prove me wrong and start consulting with the public now, in the hope that some routes will change for the better this or next year. Don’t make us wait another 12 years.

Sheba,

I see you are a fairly frequent commenter on the Buzzer blog and understand that your deep rooted passionate opinions are hard to change, but in defense of Translink, some legacy routes have been combined, straightened and simplified in last few years in areas which have gone through area planning- like the North Shore.

Every time anything is changed whether for better or for worse, a very vocal group of people that it negatively influences complain and protest. In a democratic society here, these people have a lot of power to block changes. I think this considered, Translink is doing a fairly good job of planning for the future while satiating the current users.

I also recommend reading the rest of the primer about land use and the high-frequency grid. Outside of Vancouver, the suburban single use development patterns with central commercial nodes rarely justify high frequencies. And without high frequencies on every line, you cannot have grids, unless you want passengers to wait half an hour for a transfer on a 3 km trip. If you look at satellite images, you’ll also see that most suburbs have built random strip malls and other destinations off of straight transportation corridors, perhaps fed by a highway. So why does this all matter? You cannot expect high-frequency useful linear transit services in areas that don’t support it.

I like the scenarios. With the exception of No 5, “no” is the sensible answer yet many of the complaints and “suggestions” many of the commenter on this blog sound exactly like those scenarios.

@ Chris

I only see 4 scenarios. What did #5 say?

@ All

Wow. Today is my birthday, and I thought that I would treat myself to a The Buzzer Blog post. Those 4 scenarios made me upset, because they represent the consequences of being uncooperative.

I felt that the most appropriate response was the middle finger, but I would never do that. :^D

For scenarios #1, #3, and #4, I would just say something like this.

Translink: “There is something that you need to know. Everybody wants government organizations to limit their spending and to plan. We at Translink have discovered that the costs of servicing the areas that you mention are very high, and the return on investment would leave us running a deficit. Sadly, it would also require us to divert funding from other routes that are already more successful.”. If I were addressing the city, or or a company, then I would say, “I am curious, why did you ignore our warnings and setup in that area?”.

Surrey [no names mentioned, but we’ll just “randomly” pick a city; *wink* *wink*]: “Well, because ____.”.

Translink: “Then why didn’t you at least go with your own official community plans?”.

Surrey: “…Is there nothing that you could do?”.

Translink: “Nope.”.

It’s really that simple.

As for the poor soul that got a job at Port Kells, and lives in the middle of Burns Bog, my only suggestion is car pooling for most of the way.

As scenario #2, Translink should just say, “Eugene! That’s an awesome idea. Let’s do it, team!!1!”. ;^P Honestly, as long as the idea of the rerouting has merit, then maybe it’s worth it. Sometimes the rerouting might win over more passengers as a whole. My suggestion with the #326 made me think that #2 was directed at me, even though it wasn’t. My suggestion was the opposite. I wanted to make it less confusing, and to service more riders on a busy street. Otherwise, Translink should give rough numbers on why a reroute would be unsuccessful.

I think that part of Translink’s woes are due to government successes. There was a big push to go green. Obviously, a lot of people are convinced of the need for it.

Unfortunately, the government(s) should have spent more time telling people to carpool, and to connect to another carpool along the way. The willingness to connect would allow for a greater variety of commuting alternatives, and a greater reduction in traffic.

I am not a statistician, but I bet that if everybody were willing to carpool and connect 2 or 3 times, then we could reduce our costs and traffic by well over half.

Another idea to improve carpooling might be for organizations to suggest intelligent connection points, that make it easy for drivers to pick up people. If things are standardized, then there might less mental gymnastics, and as a result people might start to say, “Yes!”.

Perhaps a solution is to buy lift equipment, and lend it to volunteers, who would be willing to carpool with handicapped people, and offer free rides. The people who would benefit the most from this are the people who will need new equipment to drive relatives around, since they would not have to buy new equipment. They could probably afford to give somebody else a ride. Therefore, they offer free labour. Translink doesn’t have to pay a driver. Hopefully, there is greater flexibility in scheduling. The passenger will get a more cutomized service. Perhaps.

The spacing for a lot of bus stops, especially in Vancouver proper, are ridiculously close. Bus stops shouldn’t be placed 300-metres apart, or in some cases even less. Let people walk a little, it won’t kill them nor hurt ridership, and space stops 500-600 metres apart – you’ll see ridership increase with increased travel speed, everyone loves faster trips. This comes from experiences in Europe and Asia.

I think that spacing stops closely on small isolated routes is something worth trying. These routes have so few passengers on certain portions that it doesn’t make sense to make passengers walk. After a full trip, the bus would have made so few stops anyways. In some cases, you can stop every 2 or 3 driveways, or offer flag stop service.

We already have pretty close stop spacings for community shuttle routes. However, even low ridership routes have high ridership times (peak times for secondary school students), and it sucks riding a bus that is constantly accelerating and decelerating every 200 metres.

But high ridership routes by definition affect many passengers, and most of the system’s passengers are concentrated on these routes. I’m more concerned about the stop spacing here, where many routes that have matured from Eugene’s low ridership routes to productive high ridership lines have gotten stuck with stop spacings of 200 meters or less on some sections. Especially during rush hours, the bus cannot even reach full speed before having to slow down for the next stop.

Walking isn’t a bad thing, especially if it can reduce everyone’s total end to end transport times. It’s not that bad for your health either.

I guess it’s okay to have close stops on rural routes, but we need strong merciless policies in place to consolidate the stops once the route grows.

@ Chris

I agree about the route growth. If the route grows, then some stops should be removed. I hope that nobody thought that I thought otherwise.

Regarding those low ridership routes, I’m thinking about only certain portions of those routes.

To All,

Thanks for the time and consideration everyone has invested into responding to this buzzer blog series. If you haven’t guessed already, our goal here is to generate a healthy debate on service planning issues – to get people thinking beyond their individual route-specific issues and transition into a more strategic discussion about the challenges and trade-offs inherent in designing a transit system. Although there are still a few people out there stuck in the micro details of this route or that, the majority of people are thinking bigger and starting to see the broader issues. We want people to get a sense of what planners think about when designing services or responding to customer requests for changes to service.

The examples here are not aimed at any one individual. Scenarios 2 and 3 are examples of requests we get on a weekly basis from all over the system. The point here is that sometimes making a change to solve one particular problem may create two different problems somewhere else. Changing a service to operate via corridor A instead of corridor B may mean better service for the people on corridor A – but what about the people we leave behind on corridor B? And what does the change do for service legibility and/or cost?

In the case of the company who wants service to their location for a small number of its employees, we are trying to illustrate the point that transit service is very expensive and we can’t always afford to run specialized service for few numbers of people. What we’re really trying to communicate is this – if you want to use transit, now or in the future, please take proximity to transit into your decision-making process right from the start. The region will have a much easier time meeting our collective goals and objectives for sustainable transportation if people locate close to existing transit service versus locating in areas far removed from the network, then requesting TransLink to send out service after the fact.

Which brings us to Scenarios 1 and 4. It shouldn’t be too hard to recognize these real life examples from our own region. Land use decisions are some of the most difficult issues to deal with. Once people or jobs have moved to an area, they are there for a very long time. If those people or jobs have been put in a place that is hard to serve by transit then we’ve created an issue that will be with us well into the future. In many cases we have few options to deal with the issue in an efficient and effective manner.

And yes, there are many services currently in our system that do not meet these principles of route design. They were likely put in place at a time when planners weren’t thinking as much about ridership as they were about coverage. But now people are requesting better service frequency, faster and more direct services, and the ability to move freely across the system without private automobiles. So planners are tasked with figuring out ways to make the existing system more efficient and productive so we can offer better service to more people within existing resources.

But there are always tradeoffs associated with any service change. For example, making a particular service more direct usually means reducing coverage. Are we prepared to make that tradeoff? Are you prepared to support the change? If there is one law of service planning it is this – those that oppose a service change may only represent a small number of people as compared to those that support the change, but they will come out loudly and clearly against it. Those that support the change don’t tend to be as vocal or persistent. So are you prepared to make your voice heard over those that might resist a particular service change that you support?

We actually do have some ideas about changes to the architecture of the network. We hope to roll those out to the public in the fall and we’re looking forward to your thoughts and ideas on our thoughts and ideas.

Thanks again for everyone’s comments.

PS. Just want to confirm that yes, that is our Peter Klitz from TransLink planning posting above :) He works on the Managing the Transit Network project and we interviewed him at the start of the series here.

I’m finally back after the heat of this weekend.

I don’t think I’m quite that stubborn Chris. If someone can show me something that works and isn’t exactly what I had in mind then I’m all for it.

In defense of my general stance, you said “some legacy routes have been combined, straightened and simplified in last few years in areas which have gone through area planning – like the North Shore.” That’s nice, but the reality is that TransLink has been in charge since 1999, and fixing up a few routes isn’t enough to make me happy – a few routes a year would begin to.

The South Of Fraser area transit plan really needs attention. Burnaby, New West and Coquitlam have messes too. I know every change isn’t going to impress everyone (myself included) but it feels as though the only big upgrades have been to build more Skytrain lines, which I applaud but not at the expense of everything else.

[…] looking to achieve one of three main objectives, while keeping in mind the four design themes, and nine route design considerations. But what’s the process like for deciding what changes go ahead? How do they come to a decision […]

[…] Translink’s buzzer: Building a better transit line: how location and land use make or break good transit service, august 2, […]