It’s time to talk about transit fares

It’s time to talk about transit fares

Regular blog readers have been asking about this for years and we’re super excited to announce we’re looking at our transit fares again!

Over the years, the transit system in Metro Vancouver has grown into a diverse and expansive network that now provides nearly one million rides every day. But since 1984, one thing hasn’t changed much.

With the rollout of Compass, we now have new tools to create a fare system that provides a better customer experience.

What do you like about the current fare system? What would you change? As part of the first of four phases in the TransLink Transit Fare review, we want to hear what’s important to you.

As you know, our current fare system is made up of six core components that determine how much you pay to use transit in Metro Vancouver.

- Distance travelled

- Transit service

- Time of travel

- Fare product

- Customer group

- Journey time

In the Fare Review, everything is on table — don’t take anything for granted and get ready to share your opinions.

Take the survey between May 24 and June 30, 2016 at translink.ca/farereview and have your say on how to improve the transit fare system.

History of Fare Systems

As noted in our 125 Years of Transit series, Vancouver’s first public transit vehicle was an electric streetcar that rolled down Main Street for the first time in 1890. Soon, it was transporting Vancouver’s early residents and visitors along nine kilometres of track throughout the city. A few months later, an expansion line was opened to New Westminster.

From its earliest days, public transit in Metro Vancouver has focused on crossing municipal boundaries to connect the region. After nearly 100 years of experimenting with zones and boundaries, in 1984 a three-zone fare structure similar to the one we have today was created. From one flat fare for all trips to over 100 fares to choose from, our transit system has tried it all.

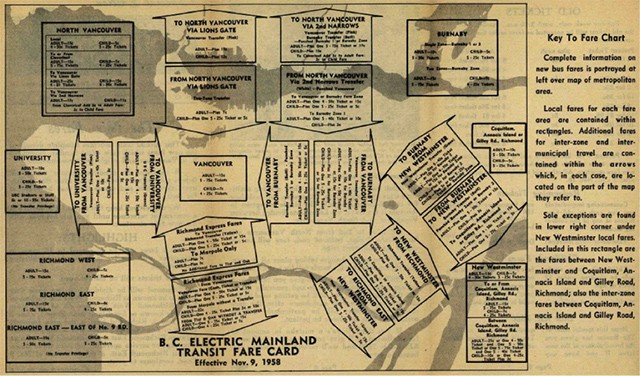

1958: 100 Fare options

In 1958, the transit system covered a much smaller area than it does today. Transit service was available in only Vancouver, North Vancouver, Richmond, Burnaby, New Westminster, and a small section of Coquitlam. This area was divided into 11 fare zones that combined in different ways to offer over 100 distinct fare options.

The price of a fare in 1958 was based on both the start and end points of a trip and the amount of distance between those two points.

In general, the price increased with the number of zones crossed. The price of a fare was related to the amount of distance travelled, but other factors also came into play.

Direction mattered. The trip leaving home could cost more than the return trip because of the direction of each trip, and zone boundaries were inconsistent.

Vancouver, for example, was a single zone while Burnaby was divided into two zones. Travel that took place within only one zone varied based on which zone it was. Transfers were based on geography, so transit riders were required to pay an additional fare if they decided to take a different route, travel extra distance, or when they wanted to return home.

Looking at the 1958 fare map today, one thing is immediately clear: it is complicated! Nothing about this system is simple to use or understand.

The fare structure in 1958 was intended to be fair. It is a good example of a system that captures the user-pay principle: everyone pays according to what they use. Fare prices increased with the number of zones crossed so that fare prices were tied to distance travelled. The high degree of detail that makes this system so complicated also makes it very precise.

The good intentions of this system were buried beneath layers of complication that may have negatively impacted efficiency. A complicated system can increase the time needed for each rider to identify and pay for the right fare, which would slows things down for everyone when this happens at the front of a bus. The lack of flexibility in the way fares were structured meant that riders who changed their minds or purchased the wrong fare would need to purchase another one to correct the mistake.

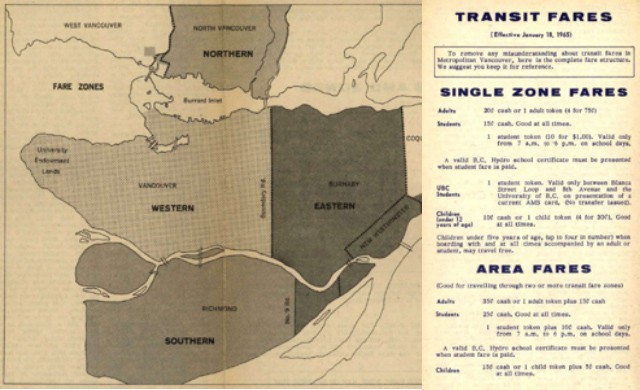

1965: Two Fare Options

It may come as no surprise that after seven years with a fare system as highly complicated as the one from 1958, the next fair system introduced made one big change: it was simpler.

In 1965 a new and simpler fare system was introduced. The 11 zones that had existed were redrawn to four, and transit riders could purchase one of only two fares available: a Single Zone Fare, which allowed for travel within one zone, or an Area Fare, which allowed for travel that crossed any number of zone boundaries. Changes were also made to make transit more affordable for students by expanding the student discount.

This option was much more simple to use and understand than the previous system. However, some felt this simplicity came at the cost of fairness. For example, someone who wanted to travel a short distance that crossed a zone boundary was required to purchase an Area Fare for the same price as someone else who took a long trip that covered a greater distance and crossed multiple zones.

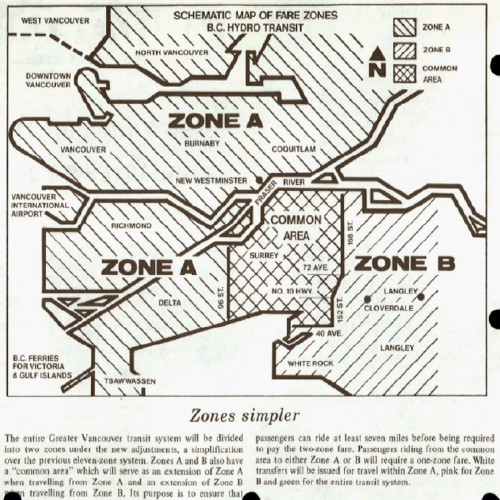

1976: The Common Area

In 1976, a new fare system introduced a solution to those short trips that crossed a zone boundary were charged the same fare as a long trip that travelled through multiple zones.

This new fare system divided the region into just two zones: Zone A and Zone B. Between Zones A and B was a Common Area, which was tacked on as an extension of the zone where each trip started.

For a trip to be charged a two-zone fare, it would have to start in one zone, cross through the Common Area, and end in the other zone. This was an attempt to make the zone boundaries less rigid. However, as the next example illustrates, decreasing the total number of zones can often mean that those who travel the shortest distances pay the most for what they receive.

1981: One Flat Fare

In 1981, a new system was introduced that eliminated fare zones and charged just one Flat Fare for travel anywhere on the system. Discounts remained for children, students, and seniors. Ninety-minute transfers were introduced to allow for adequate time to complete a trip on the transit system that now covered more area than ever before. For frequent users of the system, such as commuters, a new monthly pass was offered. The pass was priced at the equivalent of 40 trips per month, equal to 2 trips per day, Monday to Friday.

A Flat Fare system is one of the simplest forms of transit fares. With the exception of a few types of riders who receive discounts (students, children, and seniors), everyone pays the same fare regardless of the distance or direction travelled. The monthly pass made things even simpler for frequent users by providing an option to pay just once per month. This was the simplest fare system Metro Vancouver has ever seen.

Some felt that the simplicity of that Flat Fare came at the cost of fairness. When only one fare price exists for transit, the price set is an average price. As a result, transit riders taking shorter trips end up subsidizing those longer trips taken by other riders.

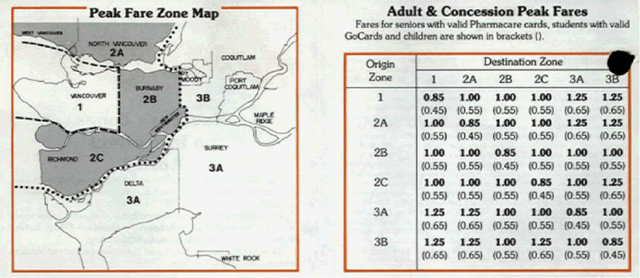

1984: 3-Zones+

In 1984, zones were reintroduced along municipal boundaries. This was intended to address the fairness concerns of the Flat-Fare system of 1981 and linked prices more closely to distance travelled.

These zones were in effect only during Peak Hours, those times of the day when transit is the busiest. To increase efficiency, an off-peak discount was introduced in the early morning, middle of the day, and late evenings, to encourage flexible transit riders to take trips at less busy times of the day when each additional passenger costs the system less.

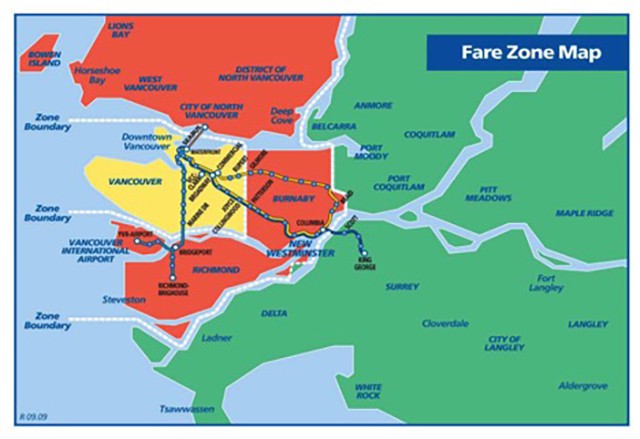

Today: 3-Zones

Today’s fare system is a simplified version of the 3-zone fare structure introduced in 1984. Zones 2A, 2B, and 2C were combined into Zone 2, a change that also took place by combining Zones 3A and 3B into Zone 3. This made the system less complicated, easier to understand and helps transit riders predict their fare price in advance. The mid-day discount was also eliminated in 1997. With the exception of these two changes, the system remains largely the same. Based on our discussions of trade-offs gleaned from historical examples, where do you think this system excels and where could it improve?

The transit system in Metro Vancouver in 1984 was essentially a network of buses and the SeaBus. Skytrain was two years away from completion and the West Coast Express and Canada Line were still far-off dreams. The system has grown, but the 3-zone fare structure has remained the same. Does this structure work for travelling on our system today? Or is it time to take a fresh look at how we determine transit fares? What change should we consider to improve the customer experience, make transit more efficient and help increase transit ridership?

Author: Sarah Kertcher/Robert Willis/Tabrina Clelland (History of Fare System)

I would say eliminate the 3 zone fare, not many people travel 3 zones and introduce all zone travel on the canada line and the skytrain.

Hopefully distanced based fares will be implemented. Currently it’s a rip to pay 2 zones just to travel one station on the Skytrain.

Make it simple.

Eliminate the fare zones and charge a flat 2.5 to 3 hour fare ($2.50-$3.55) for bus/skytrain/Canada line/seabus & ($4. to $5 on WCE) . This way it’s much easier to know when your fare expires, making it easier to transfer between each mode of transportation.

Day pass price should stay the same.

On the distanced based fare, see a word of caution here:

https://voony.wordpress.com/2013/10/03/the-short-coming-of-a-distance-based-transit-fare-system/

(So as suggested in my post, I could encourage more a “yield management model”).

Return the “family travel on Sunday” to the bus pass system … there are rarely any families with more than one child travelling anywhere on the sky train or bus, because the cost for a family of 5 is at $10.75 for one zone (that’s $21.50 for a round trip). So people end up walking or for those that can afford – buy a vehicle. You system has become unaffordable for those without the means … I know because we’re the only family I see using it (when we can afford to) and that’s unfortunate that you have left a demographic on the “side of the road.”

p.s. Thanks for listening.

Ticket purchases should be based on travel time, so that people can purchase based on how far they are going. One should be able to purchase a ticket for 10mins if they are travelling from Metrotown/Patterson to Joyce/29th Avenue, and not get penalized because they are just across a zone boundary.

How hard is it to pay a $/min fee that is the same rate regardless of where you go?

Of course, the different speeds of services should be taken account. West Coast Express would be the highest $/min, Skytrain a bit less, while bus, seabus and handydart should be lower to account for their slower movement.

I agree with many that prefer distance-based. However, cash support on buses would be limited. Cash support would only work on Community Shuttle buses, Orion V highway coaches, and HandyDART buses. On conventional and trolley buses, it is difficult to support cash and enforce distance-based. So there is going to be a need for a second method of payment aside from Compass. Debit and credit payment need to be phased in. However, there should also be a Chip-and-PIN terminal so users can insert their chip card and enter their PIN if their card does not support tap-and-pay or the tap-and-pay limit has been reached. Even when paying by Chip-and-PIN or contactless, a transfer should be issued so the need to tap or insert credit or debit card repeatedly is not needed to speed up boarding and exiting. Also, the transfer shows the transfer expiry date and time along with other information such as age category. When paying the required fare on a bus by debit or credit, the final charge should apply when the transfer expires and after scanning out the last time. Failure to scan out results in unnecessary charges when the bus the transfer was scanned on reaches the terminus and force scan out. Also, the reader should also collect the cardholder age information and automatically decide whether it should pay adult fare or is eligible for concession fare. On conventional, trolley, and Orion V highway buses, Chip-and-PIN terminal should be wired and fixed on a stand while for Community Shuttle and HandyDART buses, Chip-and-PIN terminal should be wireless and portable so wheelchair riders, scooter riders, stroller riders, etc. can still pay their fare by credit or debit even though they cannot access the front.

For reloading Compass cards and tickets, there should be an app for NFC-enabled smartphones running Android, BlackBerry, and Windows. Then riders reloading their Compass card that was not registered or is reloading their card anonymous or upgrading Compass ticket should able to reload or upgrade via an external app (e.g. PayPal, Android Pay, etc.) or an external device or card via NFC (if a debit or credit account was not set up on the device used as POS (Point Of Sales)).

Future bus transfers should not be magnetic nor issuing Compass tickets. Instead it should be QR-coded paper transfers so the paper transfers can be disposed safely in a common paper recycling container or let the transfer biodegrade. CVMs should also be fitted with a QR code reader to read not just the transfers but also change cards, 3rd party vouchers, pick-up orders for bulk ticket, card, etc. The app used for reloading Compass cards and upgrade Compass tickets should also have the function to upgrade these QR-coded paper transfers. For iPhones and iPads, they should only have the function to upgrade the paper transfers via external apps only such as Apple Pay, PayPal, etc. For Android, BlackBerry, and Windows devices, like upgrading Compass tickets, payment method includes external apps and external devices or cards via NFC.

Future bus fareboxes should not just include a bill reader but also a change chute if a rider overpaid fare. In addition, the bus farebox should also dispense a change card if the farebox has insufficient change to give back to the paying rider. The change card can be used as a discount coupon for future transit rides or redeeming cash or credit (for Compass card, credit card, or debit card) at a CVM.

Hi there,

Thanks for your comment! Lots of great ideas.

As for distance-based travel, right now we are in phase one of our Fare Policy Review that governs fares.

You can take the survey now at: http://www.translink.ca/farereview and weigh in on the options being considered for the future.

Apps are great! There are no plans at the moment to include an app payment for Compass but please send the details of your suggestion to Customer Relations so there can be a log of the request and that builds a case for the customer need. You can submit your ideas here: http://feedback.translink.ca/

Fare boxes will remain exact change only, as far as I know. No plans to change those out at this point in time.

Thanks again for reaching out and be sure to send your ideas to Customer Relations so they can be documented and forwarded to the correct department. :)