June 27 marks 130 years of public transit in Metro Vancouver

June 27 marks 130 years of public transit in Metro Vancouver

Metro Vancouver’s first public transit vehicle was an electric streetcar that rolled down Main Street in the City of Vancouver for the first time on June 27, 1890.

That makes June 27, 2020 the 130th anniversary of public transit in Metro Vancouver!

It was transporting Vancouver’s early residents and visitors along nine kilometres of track throughout the city. Then, a few months later, an expansion line was opened to New Westminster and before you knew it, transit arrived in all corners of the region.

For 60 years, the streetcar and interurban dominated the region until buses came around! Diesel and trolley buses were used and allowed residents to venture around their neighbourhoods and even further out.

Times changed again when the SeaBus sailed into service and eventually our elevated rapid transit system, the SkyTrain.

Over the course of Metro Vancouver’s 130-year transit history, what has it taught us? Transit is resilient. And it’s there when the people of Metro Vancouver need it most.

It persevered through the Spanish Flu pandemic, First World War, Great Depression, Second World War and more. Each time, it came out stronger and even better.

The world wars were periods of mass industrialization and technological advancement, especially during the Second World War. If you weren’t enlisted in the military, it was your job to support the war efforts back home.

“The transit system was just essential to Vancouver’s contribution to the war effort, which was really significant in the Second World War — shipbuilding in particular and resource extraction,” says Michael Kluckner, president of the Vancouver Historical Society.

In the First World War, few people had cars, but that changed by the Second World War. Gas and tire rationing forced people to find new ways to get around and to get to the huge number of industrial jobs that opened up. Naturally, people turned to transit.

The B.C. Electric Employees Magazine reported that the average number of passengers per day increased from 150,000 in January 1938 to over 270,000 by March 1943.

But there was just one problem amidst increasing demand — there was a labour shortage during the war years. This opened the door for women to work and they were were hired into non-traditional work to help address the shortage.

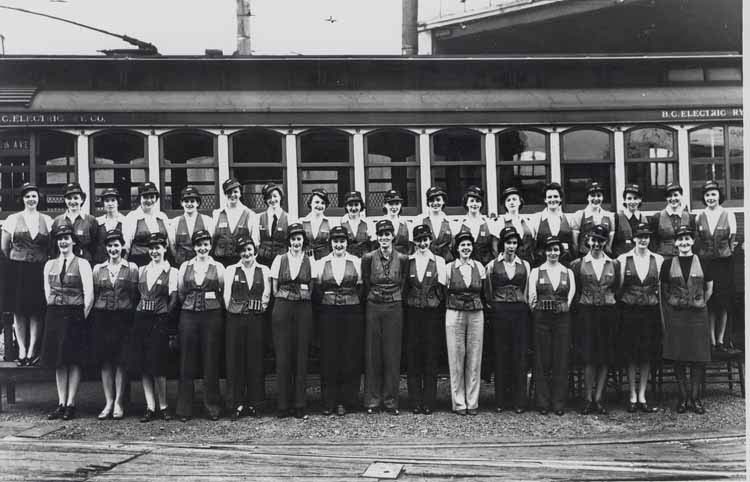

That’s why in 1943, the B.C. Electric Railway Company, which operated public transit in Metro Vancouver between the 1890s and 1960s, hired the first women to work on transit.

The women hired during this time were called “conductorettes” and they worked on the streetcars, and only on the Vancouver routes—you wouldn’t find them on the interurbans. The company also hired women to work as “electric guides,” selling pre-sold tickets at busy streetcar stops in Vancouver.

After the war, the conductorettes actually kept their jobs because they had full membership in the union, so some stayed on while others left.

In the post-war era, public transit was at also at a crossroads.

Michael explains while ridership boomed during the Second World War there had been little investment to renew and improve the transit system since the Great Depression during the 1930s. The transit system fell into disrepair.

“When World War II broke out, there was no money or even materials to invest in improving the transit system,” he says. “That’s why when 1945 came around, everything was pretty old and in need of renewal.”

There was need for a thorough modernization of the fleet of transit vehicles.

A decision had to be made about renewing the ageing streetcar fleet, along with all track and electrical equipment—but it was deemed a dubious investment for a population that was returning to automobile travel. Instead, the company decided to launch a 10-year program to convert the entire transit system “from rails to rubber,” from streetcars to rubber-tired buses.

“[The transit system] didn’t begin to pick up again in terms of public investment [and understanding the] value of it until the early 1970s with the [Dave] Barrett government and they put in the SeaBus,” says Michael.

The SeaBus came at a time when there was growing congestion in a growing region, which called for new mobility solutions such as a downtown freeway plan and bringing rapid transit to the region.

The two vehicle crossings across the Burrard Inlet — the Lions Gate Bridge and Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing — were clogged. Build a third crossing for vehicles, or put in a ferry service for a fraction of the cost. Needless to say, they chose the latter.

And during this time, an Ontario crown corporation called the Urban Transportation Development Corporation (UTDC) was developing the Intermediate Capacity Transit System (ICTS), a rapid transit system that’s between a subway, and streetcar or light rapid transit system.

With UTDC looking to showcase their newly developed system and Vancouver in need of a rapid transit system, it was a natural fit to build the first ICTS system in Vancouver for 1986 World’s Fair — or Expo 86 — which had the theme, “World in Motion, World in Touch.”

The SkyTrain started as a demonstration line, operating from Main Street Station down Terminal Avenue and back. Then it became a full line when it opened December 11, 1985 in time for Expo 86, operating from Waterfront Station to New Westminster Station.

A few years later, it was extended to Columbia Station and then in the early 1990s, the SkyTrain line went further into Surrey all the way to King George Station.

Then in the early 2000s, the SkyTrain line became the SkyTrain network. The segment from Waterfront to King George stations became the Expo Line, and the Millennium Line arrived with new stations from Sapperton to VCC–Clark.

In 2009, the SkyTrain network added the Canada Line from Waterfront to YVR–Airport or Richmond–Brighouse stations. The latest addition came in 2016 when the Evergreen Extension from Lougheed Town Centre Station to Douglas–Lafarge Lake Station.

Today, our rapid transit system continues to expand — both in the air and on the ground, on rubber wheels and steel.

This year, RapidBus launched — a new bus service offering fewer stops and up to 20% faster service than local buses. RapidBus operates on King George Boulevard, Marine Drive, Lougheed Highway, 41st Avenue and Hastings Street. More routes are planned as part of the Mayors’ 10-Year Vision.

The construction of the Broadway Subway project, extending the Millennium Line from VCC–Clark Station to a station at Arbutus, is scheduled to begin later this year. While the business case for the Surrey Langley SkyTrain was approved earlier this year.

But the question is, always, what’s next?

Public transit has shaped the way this region has grown and will continue to grow.

Over the years, myriad companies – both private and public – have operated transit in the region, but the goal has always been the same: help make Metro Vancouver one of the most liveable cities in the world.

Here at TransLink, we’re proud to be a part of a storied history of public transit that spans 130 years, carrying on the legacy of those that came before.

Because the better the region moves, the better our communities move with us, benefitting the economy, the region and everyone that calls this place home.

We’re a team of more than 7,000 employees united in support of our customers — more than half-a-million of them on a typical day, connecting them to the people and places that matter most.

Transit was here to take you to your first date, first job, and first concert or Canucks game at Rogers Arena. Many of you found love on transit, including Stefan and Carolini, Meghan and Steve, as well as Rebekah and Scott.

And at the COVID-19 pandemic’s peak, transit was here to keep the region moving, carrying more than 75,000 people each day. Our customers included essential and frontline workers such as nurses and grocery clerks, but also people who have no other means to get around and they needed transit to pickup their groceries and medication.

As B.C.’s economy restarts, transit service has been restored with the help of the provincial government, bus seating restrictions have been eased and a Safe Operating Action Plan has been implemented.

Ridership has increased by 85 per cent since early April and that’s a start.

As region continues to recover from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re working provide safe and reliable transit solutions for our staff and customers as they return to work, to school and to moving around the region.

That’s why as part of the 2020 Open Call for Innovation, we’re looking for innovative ideas to address the new challenge statement: How can we improve health, safety, and public trust as we welcome customers back to the public transit system in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic?

“As we welcome back more customers onto transit, we want to collaborate with local businesses, likeminded partners, and innovators of all sorts to help with our recovery efforts,” says TransLink CEO Kevin Desmond. “The goal is to produce creative solutions and have them implemented on our system as soon as possible.”

As we collectively reflect on 130 years of public transit, the future is a responsibility we all share together, so together we must find ways to adapt.

Written with files from Jhenifer Pabillano, former editor of The Buzzer

Is it possible to use the Rapid Bus #701 from Coquitlam Central skytrain buses travels to Mission.

It’s Lafarge Lake-Douglas Stn, not Douglas-Lafarge Lake.